2019.51: the temperature of kindness

Chinese artist, Yang Yongliang (via @WeirdlandTales)

Would you look at that—Christmas is just around the corner! Perhaps you’re on your way to a warm reunion with those you love, or anticipating a tense standoff broken only by an armistice of present unwrapping. The holidays can be rich and full, or dark and lonely. Sometimes both at the same time. Each holiday gathering a different relational pattern.

I’ve always felt tuned to these social flows, to those souls floating at the rim of the whirlpool. To the rough edges of conversations. To the sweetness of the middle and the sense of where that middle ends. I know this sensitivity is what made me want to design games in the first place. It’s no coincidence that we talk about a conversation “flowing.” It’s just as fun to talk about the eddies, the stagnant areas, the dead pools. Shift a mechanic here, a norm there, and you can get things moving again. A good game is like good plumbing, or just to torture the metaphor further, like a good pour of Dräno.

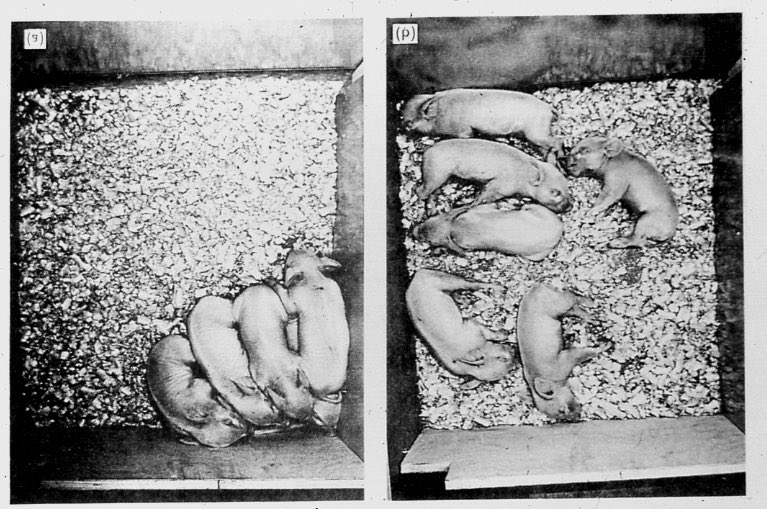

I want to show you an image that profoundly influenced me, years ago when I was getting into design. On the left, stressed out piglets huddle for warmth in a corner of their pen. On the right, happy piglets splay without a care in the world.

Now, what’s the difference between these two pens?

Did you guess it? It’s just the temperature.

The image comes from an interview with Usman Haque, an early internet of things pioneer, where he talks about his vision for intelligent spaces:

My focus as an architect has always been to consider what I’ve called the “software” of space (sounds, smell, light, temperature, electromagnetic fields, social relationships, etc.) rather than the “hardware” (floors, walls, roof, etc.) as it has traditionally been considered. The image (above) really sums up why I think this is important.

It’s the same piglets, in the same box, but on the right hand side the temperature has been increased. This small change in how the space is “programmed” has dramatically changed the way the ‘inhabitants’ relate to each other and how they relate to their space. This approach to architecture became my challenge: how to translate such strategies into the general architectural discourse and how to bring into reality such possibilities for the construction industry.

Hosting in-person tabletop games, this couldn’t be more obvious. You take a room, bring the coziest things you can—lighting, warmth, snacks. You layer in the game’s rules and norms and you enter a different world.

Aside—this is why I absolutely love how the Powered By The Apocalypse system recognizes this and calls the game loop “The Conversation”. It’s made explicit in games, but every conversation is guided by some system of implicit and explicit rules and norms. Games are an alibi to play with tweaking this social code.

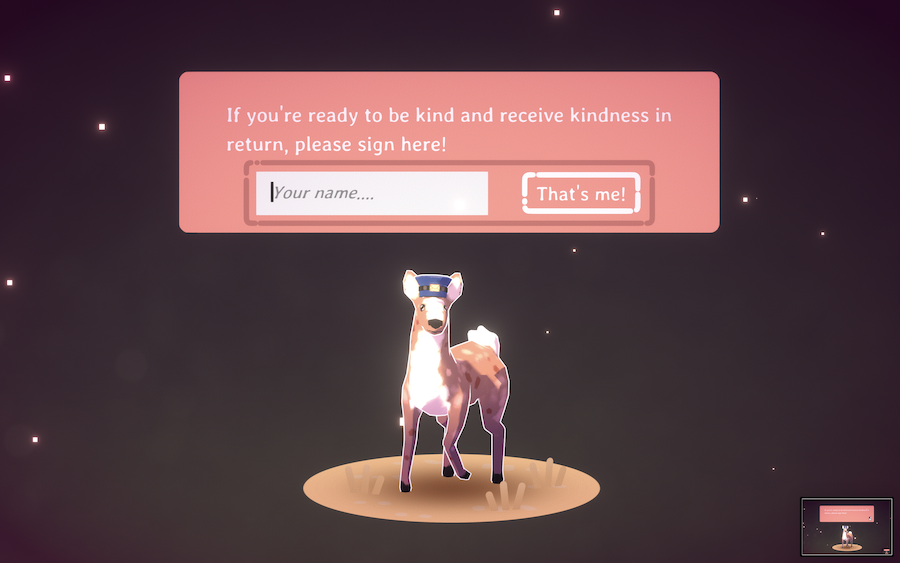

But what about those darn digital spaces, in all their legendary toxicity? Well, I present to you Kind Words. I’ve never loved something so much at first sight.

It’s a cozy game where you write kind letters to real strangers dealing with real shit.

Kind Words makes no bones about its purpose. When you begin the game, it tells you that it’s a place for “real people” to discuss “real problems” and quickly adds that “this is not a place for mean jokes, bullying, or flippant responses.” It encourages players to report people who engage in that kind of behavior. This, evidently, makes a strong first impression; I’ve never encountered any trolls while playing Kind Words. Moreover, as the game’s own players have pointed out, trolling in Kind Words isn’t all that fun. When you respond to requests in the game, you don’t get a reaction. You just send off some (hopefully) kind words in response to another person’s concerns, and that’s it. If someone receives a troll response, they can just report it and get on with their day.

What’s remarkable is how Kind Words subverts the current paradigm for dealing with toxicity in online, which is to try to shape expressive ability, usually by limiting it—think Journey’s nameless, wordless companion, Death Stranding’s “Like” button, Hearthstone’s limited palette of emotes.

Kind Words lets you speak freely, and it’s working:

“Out of well over half a million letters written, we’ve had to address just shy of 3% of that content, and most of that is off-topic—not trolling.”

It’s a brand new kind of experience, somewhere between checking your email and playing classic floaty-stranger-kindness-game Journey.

I’ve been following the development of game social systems for years. As with the internet as a whole, gaming has grown from a bunch of unmoderated niche communities to a gigantic social space and toxic garbage fire, but it’s only in the last 5-10 years with the explosive growth of streaming, e-sports, and gaming as a whole, that triple-A game companies have begun seeing this as their responsibility to solve, rather than just “gaming culture” and “boys will be boys”. Gaming culture is now simply culture. It belongs to everyone.

Perhaps this is a reach, but for me, the biggest symbol of this is not a multiplayer game at all: it’s last year’s reboot of God of War, a game series which had been all about its rage-filled protagonist slashing through the pantheon of Greek deities. The new game is a startling reinvention; the surprisingly heartfelt tale of a grizzled old codger mourning his errors and learning to love and nurture the next generation. Cory Barlog, game director:

When I came back to Sony I realized that the biggest thing that happened in my life — I was shipping Tomb Raider, and my son was born. I was either going to make a ripoff of Tomb Raider or incorporate my son into this story.

As I started thinking about it, I realized that there’s a lot that changes. Everybody says a kid is life-changing, but your perspective on things changes. It made me think about this idea that — okay, here’s a character that everybody dislikes. We built him as an anti-hero. The whole goal — at the time there were not a lot of anti-heroes in games, so that’s what we leaned into. But it was this idea of giving him a reason to want to change.

As the old generation of developers hands gaming to the next generation, they find themselves questioning what they created in the past. These new worlds are an uncharted frontier, virtual and real merging together into a high-frequency maelstrom that is as incomprehensible as it is addictive and all-encompassing. Games like Fortnite are spaces. And those creating those spaces are waking up to their responsibility to make those spaces good.

As VP Tami Bhaumik at (insanely successful, btw) massively-multiplayer-game-creation-thing Roblox says:

“Your generation and my generation have no idea how this younger generation lives and operates,” Bhaumik says. “In our world, there was a line between the digital and physical worlds. But our society has evolved so quickly that young people now have no line. Their virtual world and their physical are one and the same. They socialize, they learn, and they play seamlessly between digital and physical. It suddenly just happened. So now it’s about taking responsibility and teaching our younger generation how to be able to create positive experiences.”

What taking responsibility looks like

This is why I was so excited to learn about the Fair Play Alliance, which is a coalition of over 100 game companies pooling resources to develop best practices for reducing toxicity. The talks from the most recent summit at GDC are an incredible resource, particularly this primer on the latest patterns in online social mechanics by Riot Games’ Naomi McArthur and Kenny Shores. Let’s look at some examples.

Example one: the negativity bias of text chat. Text chat has been the foundation of communication since the very first online games. It’s robust, reliable, simple. But who, in an intense game where every single second counts, has time to chat?

Turns out it’s the players whose characters were just blown up, spattered, slashed in half, or otherwise forced to shuffle off their coil, and have equal parts time on their hands and frustration. Dead, frustrated players chat more, which means text chat itself has a negativity bias!

So they added Emotes, which allow players to quickly communicate without having to type out full sentences. Emotes are graphics, similar to a sticker in a chat app, that appear above your character for everyone else to see. Players map them to individual keys to trigger them effortlessly. Here’s what they look like (from the 2017 feature launch video aptly titled “Stop Dying While Typing”)

But gotta look for those second order effects! Emotes’ splashy imagery also made for a perfect tool to mess with and abuse other players (oof, this brutal example from another game). So the devs added the ability to only see emotes from your own team, freeing you from the abuse of your opponents. But that didn’t stop competitive teammates from attacking their own if they felt they weren’t performing to a high enough standard, so they also progressively added a wide variety of celebrations that made the tool more useful and fun. Now, teams routinely can use emotes to mark victories.

You can’t just suppress negativity—you also need to create tools for positivity.

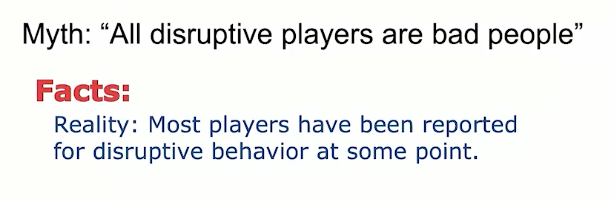

Example two: moderation mechanics, from Blizzard’s Natasha Miller and her talk on common player behavior myths. Back in 2013, Riot was pioneering its “Tribunal,” a system which not only helped assign penalties automatically but also packaged them up into shareable pages that made it easier for those who had been banned to share their sentence for community judgement if they didn’t understand it, or felt it was unfair. Very cool. Very automated.

Now, nearly a decade later, the conversation has shifted once again. It’s as important as ever to have tools that deliver clear, swift, and transparent punishment, but the industry is recognizing that it’s just as important to model positive behaviors. You don’t get the community you want just by telling folks what not to do; you need explicit standards for how you want folks to behave, and the tools by which players can reward each other for living up to these standards (e.g. Overwatch’s system of endorsements).

Tying it all together is a growing understanding that the solution must be socially nuanced. We’ve moved from “clever” solutions (“Let’s just put all the bad players together and watch them suffer, haha”), to solutions that are more rooted in true human psychology and dare I say even a little bit of compassion (“Let’s recognize that most people have bad days, and create an environment where they are exposed to good behavior and empowered to be their best selves”).

It goes without saying that American society at large could use this kind of nuance in how it approaches rehabilitation…

Example three: anonymity! An easy scapegoat, but turns out that there is no less toxicity in Korea where online gamers are required to link their player accounts to their government IDs, or of course in Facebook where most people use real names. Anonymity is simply a proxy. What matters are underlying variables:

- how likely you are to see people again (repeat interactions)?

- can express your identity?

- how easily you can define in-groups and out-groups?

- are there are ways to meaningfully connect, etc…

The list goes on. Anonymous spaces often do worse on these elements, but not necessarily. It’s slow and nuanced, but engaging directly with these underlying social patterns is what actually improves the player experience. It’s so exciting to see the industry take high-level dogma and break it down into the underlying pattern language.

And this brings me back to Kind Words, which is entirely anonymous, but which could not express a clearer contract, upfront, and without mincing words. Sign on the dotted line, and be kind.

So what’s the takeaway? It’s this: try to notice how much social warmth is coming not just from within yourself and others, but from what’s around and between you. From the actual software of these digital spaces to the metaphorical “software” of physical space—are there snacks, what sounds are playing, is this chair comfortable—and the unseen rules and norms by which you are interacting.

We have to remember that we’re playing with a stacked deck. Our brain has a negativity bias. It is exquisitely evolved to keep us safe, not happy! As psychologist Rick Hanson says: “the brain is like Velcro for negative experiences but Teflon for positive ones.” We need positive cues in our environment to counter this.

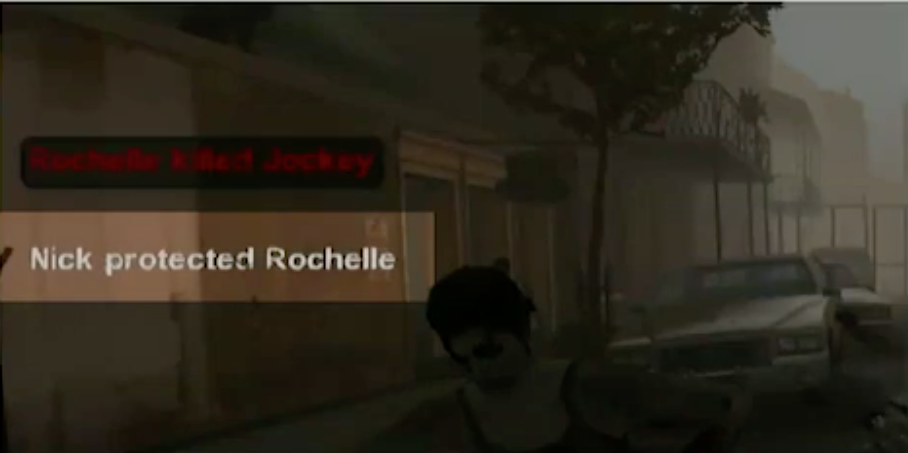

Game spaces are such interesting case studies because developers have godlike power to choose what to draw our attention to. They can make the negative signals loud, or celebrate the positive ones, as in this story Naomi McArthur tells about “Left for Dead 2”:

If you have a teammate behind you who hits you with friendly fire the game registers this pretty subtly, especially compared to other types of damage you take in the game.

However, if you have a zombie gnawing on your face and your teammate protects you from them, the game will celebrate this and call it out loudly to you to celebrate this teamplay moment.

How might we create systems that point our attentional cameras towards the good things those around us are doing?

An extremely unsubtle example of pointing the attentional camera

Back when I used to do improv my team (Emergency Sandwich, ha), had a ritual that we used to warm the ultimate blank canvas: the black box theater whose blank walls and bentwood chairs would somehow have to become a new world when the curtain went up. This wasn’t easy. You had to prime the engine, to prepare correctly for this transmogrification we’d perform together. At the end of a long Tuesday, some of us would be a little frazzled. Rushing in from school. Or perhaps the day’s work hadn’t gone quite as well as we’d hope. We were still separate, and needed to be one. That takes love. And intention.

Here was our ritual. We circled up, and each person in turn received an expression of love from every other person. “You really nailed that joke last week!” “I like the way you smile.” “Those pants look really good on you!”

It took a solid 10-15 minutes to do, but by the end each of us was shivering with euphoria, the day’s troubles forgotten, absolutely pumped to be on stage with each other. In that moment, I’d have donated a kidney to any one of those beautiful humans.

Just like the affordance-creators of game worlds, we could decide to play by a different set of rules. A clumsy, deeply unsubtle, and time-consuming game, but one that lit a fire between us.

Kind Words indeed! ❤️

‘till next time! Happy holidays my friends!

You've reached the end, my friend. Sign up to get the next one right in your inbox