2020.3: The paradox of language

Metabolic Pathways poster by Roche

This week, a paradox around language: when do you need fifty new words, and when should you use none at all?

Fifty (Pantone) shades of snow

It all started when I decided to revisit that landmark 1911 Franz Boas ethnography turned meme of the fifty Eskimo words for snow. I wondered, was that old statement still true? Kind of.

Inuit, the language Boas studied, is polysynthetic, which means a single word is assembled from smaller pieces, each piece more like a word in an English sentence. So the concept of fifty distinct “words” didn’t technically apply, sparking a debate that rages to this day amongst linguists. But according to Washington based anthropologist Igor Krupnik, the insight still stood; Boas had taken care to look at fragments with meaningful distinctions.

Phew.

But the overall point, that societies have many words for things that matter to them? Fifty is only the starting point! Krupnik himself documented about 70 terms for ice in the Inupiaq dialect of Wales, Alaska. Other cultures have even more:

The Sami people, who live in the northern tips of Scandinavia and Russia, use at least 180 words related to snow and ice, according to Ole Henrik Magga, a linguist in Norway. (Unlike Inuit dialects, Sami ones are not polysynthetic, making it easier to distinguish words.)

The Sami also have as many as 1,000 words for reindeer. These refer to such things as the reindeer’s fitness (“leami” means a short, fat female reindeer), personality (“njirru” is an unmanageable female) and the shape of its antlers (“snarri” is a reindeer whose antlers are short and branched). There is even a Sami word to describe a bull with a single, very large testicle: “busat.” (via the Washington Post)

Language grows around the things society deems important. It enables coordination around increasingly nuanced topics. It turns individual into collective intelligence—both in the moment and across time, as you need language to pass down complex concepts to the next generation.

This power is as real now as it was then. My favorite modern example comes from the world of commerce. Meet interior decorator’s superpower and 3am-bloodshot-eyed-designer arch-nemesis, the Pantone color fan:

In the 1960s, the central struggle of post-WW2 western civilization was no longer snow & ice but rather the free market & mass production. Television and mass media exploded. Munitions factories began making toasters, cars, and Coke. Companies suddenly found themselves with both the need and the tools to standardize their brands.

And a crucial dialect of brand is color:

Back in the early 1960s, Pantone was a printing company in Carlstadt, New Jersey, with a specialty in color charts for the cosmetic, fashion, and medical industries. Lawrence Herbert joined the company in 1956 and noticed how difficult it was for designers, ad agencies, and printers to communicate—identifying exact colors from names alone is tough. For example, there are red-based purples and blue-based purples, warm and cool shades, lighter and darker tones. Mistakes happened, there were tons of inefficiencies due to reprints, and Herbert knew there had to be a better way to do things. He bought Pantone in 1962 and launched the first PMS guide in 1963 with 10 colors in an effort to reduce the number of variables happening in the printing process. Creating an objective, numeric language means that any printer anywhere in the world can accurately produce a color.

Picture a shelf of Coke bottles where every other label was a slightly different shade. Yes, they’re technically all “red” but they’re not the right red. This might make you think some bottles are less fresh than others; therefore the brand isn’t reliable. (You even might grab a Pepsi instead.) Real Coke bottles in New York are the same red as ones in London or Mexico City or Mumbai: Pantone 185. (via Fast Company)

If a society’s central dynamic is the cold, language grows into nuanced descriptions of snow & ice.

If a society’s central dynamic is the market, language grows into nuanced descriptions of branded color.

Every domain develops specific languages, incredibly shiny & chrome (sorry, couldn’t resist). Sometimes these end up as colloquial terms, other times as highly technical jargon.

From “cook” to:

Acidulate, Al dente, Amandine almonds, Amylolytic process, Anti-griddle, Aspic, Au gratin, Au jus, Au poivre, Backwoods cooking, Baghaar flavoring, Bain-marie, Bakin, Barding, Barbecuing, Baste, Blanchin, Boilin, Braisin, Bricolage, Brine, Broasting, Browning reaction, Caramelization, Carry over cooking, Casserole, Charbroilin, Cheesemaking, Chiffonade, Red cooking food, Velveting, Clay pot cooking, Coddling, Concass, Conche, Confit, Creaming, Curdlin, Curin, Deep frying, Deglazin, Degreasin, Dough sheeting, Dredging, Dry roastin, Drying, Engastration, Earth oven, Egg wash, Emulsify, En papillote, En vessie, Engastration, Engine Cooking, Escagraph, etc… (via Wikipedia)

From “let’s play pretend” to:

0-level spell, 5-foot step, aberration type, ability, ability check, ability damage, ability damaged, ability decrease, ability drain, ability drained, ability modifier, ability score, ability score loss, abjuration, acid effects, action, adjacent, adventuring party, Air domain, air subtype, alignment, ally, alternate form, angel subtype, Animal domain, animal type, antimagic, aquatic subtype, arcane spell, arcane spell failure, archon subtype, armor bonus, Armor Class, artifact, Astral Plane, attack, attack of opportunity, attack roll, augmented subtype, automatic hit, automatic miss, baatezu subtype, Balance domain, barbarian, bard, base attack bonus, base land speed, base save bonus, battle grid, blinded, blindsense, blindsight, blown away, bolster undead… (I could go on)

(Related—my friend @randylubin mused on Twitter: “Maybe some day dnd will become the generic name for storytelling games, like kleenex or q-tip. I’m not sure if that would be worse than the current state of things. “Is The Riot Starts a dnd?”)

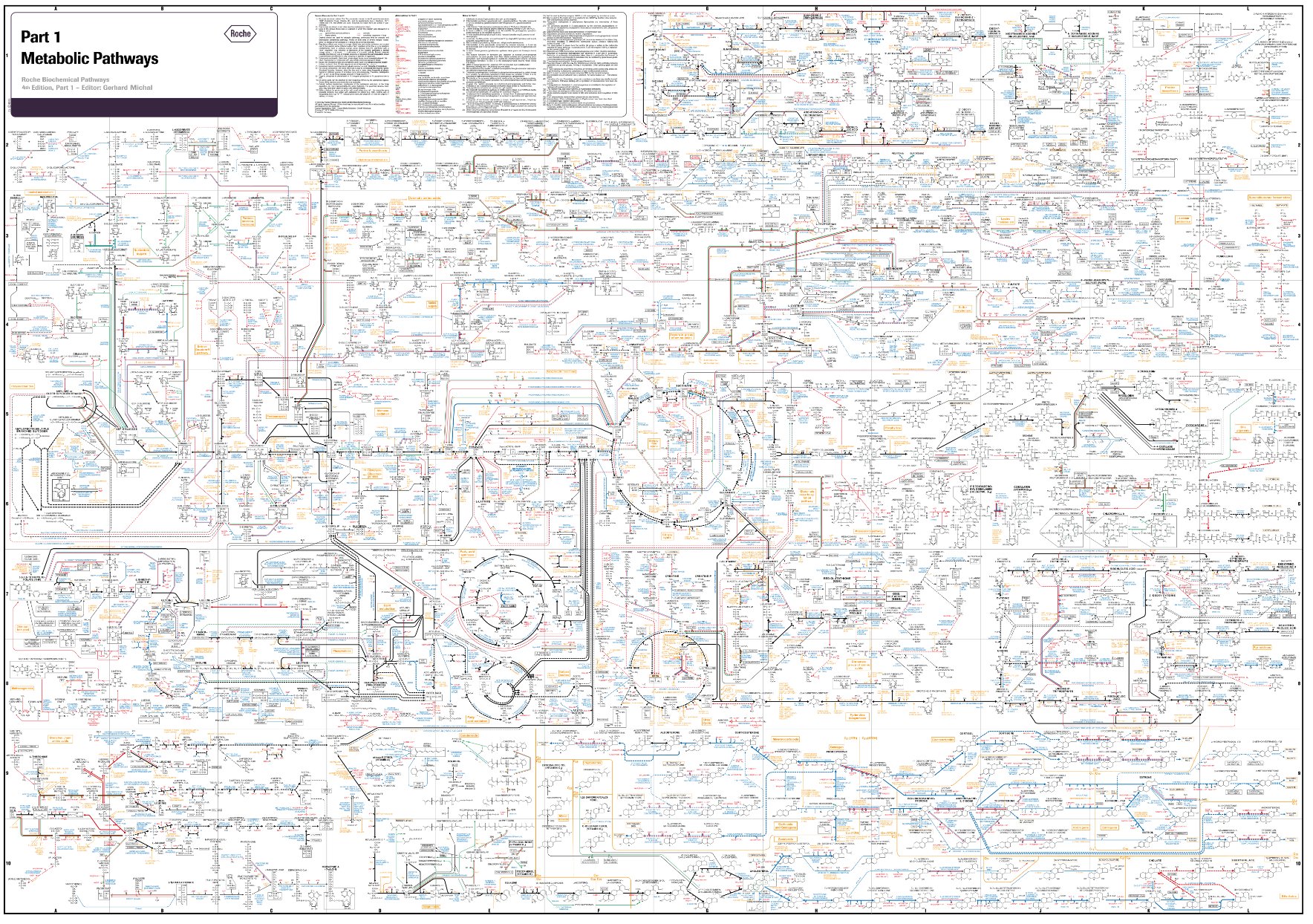

And let’s come back to the chart at the top. It’s a diagram published by pharmaceutical giant Roche, of the known metabolic pathways in the human body. This chart is naming at its most intentional, joined with a functional grammar of the interaction between its words, a razor to wrangle complexity. What gets languaged gets managed.

Finally, language is powerful and also is power. As a white cis straight dude, it’s been thrilling to learn the expanding language of all the things that are not that. Terms like “white fragility”, “cultural appropriation”, and even “whiteness” itself are brilliant revealers that make the status quo unfamiliar again, allowing me to see the water that I swim in and the entrenched biases I perpetuate.

Language is how society wrangles things.

Language is how the collective brain thinks.

Shouldn’t we strive to greater linguistic precision, until we have named and categorized every single thing, and then use that to precisely negotiate our society’s priorities?

We should! But to a point.

Let’s start with pain

I’m sure you’re familiar with the pain scale. I sure am—it’s the ceremonial 0-10 coin of passage that I must lay into resident Charon’s skeletal hand for passage across the dead river of clerical data entry and into my doctor’s appointment proper (melodramatic, yes, but a not inaccurate metaphor for the Epic EHR.)

I’ve got a variety pack of neuropathic pain symptoms that vary day by day, are contextual, and don’t always correlate. How do I say that I don’t hurt at all when I’ve exercised in the morning and am lying down, but am in excruciating pain when I sit in a specific way on a particular chair? And that all it takes is a slightly different chair, and I’m okay? These distinctions are crucial, as they are the roadmap of the subtle changes in my life that will actually help improve the situation.

The brain perceives things far from linearly. Have you heard of this guy: the sensory homunculus? His Mr. Potato-head proportions represent how much the brain perceives sensation from different areas (with the obvious PG-13 adjustment). Bigger means more pinpoint definition to signals from that area, which is why you know precisely where on your hand that cut is, but need to look at your arm to see where it’s bothering you. So how do you compare a blown knee to a paper cut on your pinky?

To answer the 0-10 question, I have to throw away so much detail, so much subjective perception, so much empowerment! My heart sinks as I hand over the number, and my brain, responding to incentives, ditches the rest of the story as worthless junk. The doctor-turned-data-entry-clerk and I sit together, equally frustrated, but with barely ten minutes left in our allotted fifteen, have to move on. I tell myself the doctor doesn’t need that information and knows better through their external, objective—scientific—diagnosis.

Okay, there’s an obvious fix: ask for more nuance, right? Instead of just one 0-10 scale, let’s do several! Give me a picture of a person to draw on, so I can pinpoint it. Let’s ask for more detail on the pain itself—is it burning, stabbing, throbbing, numb, itchy, tingling, prickly, shocking, aching, electric, visceral? I know, let’s do a fifty point scale! A hundred point scale! Or just let me write a long-form literary essay from the perspective of the injured nerve (actually, why not). Oh, what the heck—let’s just add more buttons, checkboxes, and dropdowns to the intake!

It’s not working.

The clue for why it’s not working is that when a doctor does take the time to ask for the full story, I find myself unable to answer their questions. The intake forms have so conditioned me that they’re all I can see. But because the terms they use are so imprecise, they don’t map to my experience in the real world. In the moment, they slip away like a half-remembered dream, and I find that I’m left holding nothing at all.

The system is designed for the medical establishment to categorize and standardize treatment. But it doesn’t help me, the individual, to see more clearly what’s happening within me. Quite the opposite—it’s telling me, subtly, that the nuance doesn’t matter. And when a system tells you repeatedly that something isn’t valuable, you don’t just lock it away inside you; you delete it.

I recently did an exercise where our teacher asked us to walk for 20 minutes in a garden and bring our attention as carefully as possible to all the sensory experiences. The faint smell of individual flowers; the waxy texture of a particularly dewy leaf; the rough grain of on the wood of a fence; a ladybird’s jerky search for sustenance. That was it. Just sensing, as fully as possible.

It took more like 40 minutes for the instructor to drag us back into session as we became utterly entranced by the sensations, the same ones we’d barely noticed just a little while before as we rushed to class. Time disappeared.

When you take away the impetus to name, you notice that what you see as “grass” is made up of millions of individual blades, which—if you look closely enough—are all different in ways that words can’t capture.

The larger principle? Focus on an unfamiliar dynamic range of experiences, and you’ll automatically start to see new gradations. It’s what happened with ice & snow for the Sami, with branded color in the 1960s, and to me when I stared at the grass and tried to ignore the part of my mind that was yelling, “IT’S JUST GRASS!”

It’s never “just grass.”

The language structure is just a scaffold, and there continue to be infinite divisions between the words that are valid.

I’ve started to apply this way of seeing without categorizing to my body, and it’s been startling to realize that the signals are there, still, and that if I listen, they will speak to me. But in exchange, I have to promise to try to remember the feeling they give me, not the description of the feeling.

The paradox

The question for me is how these two ways of approaching the world—seeing and naming—intersect because I’m learning that there’s a real tradeoff between the two.

It seems that prematurely forcing yourself to name things damages seeing, and at the same time, the names you abide by prevent you from seeing clearly, like a person searching for their car keys only under the streetlight and not in the darkness around it.

As UX designer, I want the world to benefit from language that fits perfectly, like comfortable rubber grips right on the handles I need to pull and the buttons I need to press. Good language tells me exactly what to do, so much so that I don’t need to “know” at all—I just do it. But I also want to know that I’m not getting stuck uncritically inside a framework that is at best inaccurate and at worst actively harmful.

I want to live in a society that has a good process for creating common names for common purpose, but also values the practice of seeing without naming at all. There should be space for individuals to deepen their experience of the world without having to shove it into ill-fitting categorization. Let experience flow into language when it has to, and no earlier.

There’s another part to this, which is perhaps even more critical:

In any human interaction, the required amount of communication is inversely proportional to the level of trust —Ben Horowitz

Valuing deep seeing also means honoring each other’s rich experiences without needing them dissected like so many butterflies pinned inside display cases. To make this concrete: I am glad that chronic pain is named so that it is no longer invisible, but I don’t want more detailed forms to fill out—I want a more compassionate, trusting, and spacious healthcare system.

It’s about balancing the paradox. Celebrate language and fight for it to represent what matters! At the same time, foster that magical space for all the things that cannot be put into words (yet, or maybe ever.)

This all makes me think about the way so many fictional and spiritual magic systems treat language. Almost all have the concept that you can’t just say “abracadabra.” That words are not enough by themselves.

Take “Naming” in Patrick Rothfuss’ Kingkiller Chronicles:

Common names are names of simple materials, such as stone (Fela), wind (Kvothe), iron (Devan Lochees and Inyssa). However, even these names are extremely potent and extremely difficult to call: the name of the wind can stop the wind or start a thunderstorm. And to even call the name of stone, the arcanist needs to know everything possible about how the world can affect it: “how the light reflects from it, how the wind cups it as it moves through the air, how the traces of its iron will feel the calling of a loden-stone“ (via the Kingkiller chronicles wiki)

You need to know the depth behind the name for it to work.

And who doesn’t want to be able to call the wind?

Your creative prompt

I bring this all up because I think storytelling games are exquisitely placed to help improve this dynamic. A game can ask you to create a brand new language or put you in situations where communication is restricted, forcing you to experience yourself, others, and the world, in unfamiliar ways.

The best example of the former? Thorny Games’ multiple award-winning “Dialect”, where you live out the difficult journey of an isolated community, first as they develop their language (literally!), and then have their uniqueness contaminated by re-exposure to the rest of the world.

A foundational mechanic in the game is the creation of new words, that you write on paper tents and use more and more as the game goes on. The manual is full of specific instructions on how to form specific words, and even includes a ten-page article by linguist Steven Bird on how to deepen your knowledge and appreciation of language.

For example, you might:

- Use an acronym: NATO, or Benelux

- Clip the word or the phrase: e.g. Gasoline → Gas

- Incorporate a sound: “A society surrounded by horses might incorporate their sounds into their speech”

- Screw words up

- Convert them (they quote Bill Watterson: “Verbing weirds language” ❤️)

So you have a loop where you develop concepts that are highly specific to the values and circumstances of your society, and then reify those concepts into brand new words. Magical!

The latter? “Still Life”, by Wendy Gorman, David Hertz, and Heather Silsbee where players embody… rocks.

In this game one player takes on the role of the Elemental Forces (EF). The other players take the roles of rocks pondering the meaning of their existence with each other and their environment, as their lives are determined by the whims of the Elemental Forces.

Each rock will have a question about the meaning of its existence. The focus of play will be striving to find an answer to this question. Players may do this by interior meditation and by talking to other rocks about their questions. Both methods are encouraged. The players may or may not ultimately find an answer to their questions. The important thing is to explore the possibilities presented by your question.

Example questions, from the game:

- Piece of Brick. What if I can’t carry them forever?

- Marble. Why haven’t I been chosen?

- Granite. Can I be tough enough to withstand the elements?

- Unidentified Pebble. What am I?

- Shale. As parts of myself break away, am I still the same rock?

- Sandstone. What does it mean to be both stone and sand?

- Quartz. Do I only exist for the human gaze?

- Petrified wood. I was once alive, but am now a rock. Which side do I truly belong to?

- Fool’s gold. If I try hard enough, will people think I’m authentic?

I love that huge chunks of the game may elapse in almost total silence, with players’ meditations on their question expressed in pure movement. (And note the fractal descent again into domain languages with the many specific words for “rock”, each of which has such different connotations). Sometimes, the right thing to do is to dance about archi… life’s most profound questions.

Still Life was a massive inspiration for my own game, “They Say You Should Talk To Your Plants”, which won the Golden Cobra for best use of silence and non-verbal elements. I wanted to explore this space in between words by having characters—the plants—who cannot speak.

More words. No words.

So this brings me back to the fifty words.

There aren’t that many games that play with this paradox. On the language side, I couldn’t find much beyond Dialect (the other obvious one is “Sign”, also by Thorny Games). As for games about seeing without naming, there’s a ton—but in adjacent domains like art therapy, dance, improv, poetry, music, and the like.

This is an opportunity! What would happen if we created games that forced us to generate new language?

- Fifty words for the ways two lovers can argue?

- Fifty words for the textures of a sandwich?

- Fifty words for how an AI controlling a spaceship feels their “body”?

- Fifty words for the feeling of missing a good friend?

- Fifty words for the parts of having a new insight?

And the flipside—what happens when we try to move away from words?

- To encounter in its entirety, without naming, an argument between two lovers?

- To encounter in its entirety, without naming, the experience of biting into a sandwich?

- To encounter in its entirety, without naming, the experience of being an AI in charge of a generation ship?

- To encounter in its entirety, without naming, the feeling of missing a good friend?

- To encounter in its entirety, without naming, the experience of having a new insight?

Just putting the prompts next to each other is such a clue about how different those experiences might be.

And perhaps one level up, how might create experiences that explore the duality of naming and seeing, of the social and individual?

- What things should we as a society have better names for so we can wrangle them together?

- What things should we as individuals practice experiencing in greater depth, without naming at all?

(And how should we create trust and spaciousness so the two can live in balance?)

So much to explore! More than can be put into words ;)

Notes

- To my delight, Matt Klein, a former member of Yo’s team, read my eulogy and added some context. “I believe Yo was ahead of its time, and its trivial novelty was both a driver and barrier to its potential success. It was absurd. But as we look to unplug and find some humanity in tech (increasingly so over the last five years), I’m optimistic Yo would fair much better today.” Thanks, Matt!

- My friend and reader, Dharmishta, shared with me Miranda July’s “Somebody”, a short film that inspired a real app where you could ask strangers to be your surrogates. The app is dead now, but the short film remains entertaining and provocative.

- This piece was getting very long, so I punted this, but if you want more on how language shapes thought, listen to this fascinating talk by linguist Lera Boroditsky.

- Something I only learned while researching this piece is that the pain scale as we know it only becomes ubiquitous in the 2000s, with the passage of H.R. 3244, a law that—practically in a footnote—defined the calendar decade beginning January 1, 2001, as the “Decade of Pain Control and Research”. Via Radiolab

- I didn’t go down this line, but Ian Bogost has a fascinating article that explores how adding more emoji is changing the fundamental nature of emoji communication, from ideography to illustration.

You've reached the end, my friend. Sign up to get the next one right in your inbox