Metatopia 2018

My first time at Metatopia and I loved it! I’m still sleepless, feeling the con crash hard. I played some amazing games with staggering emotional range (particular credit to Alex White’s “A Cool and Lonely Courage”, which ended with 20 seconds of silence to process at the end. Thank god for a whimsical game of Fiasco In A Box immediately after).

Other highlights: Chad Wolf’s wild diversity of ideas (in one LARP I was a fairy light, blinking in and out of existence, in the other we manipulated Ursula LeGuin’s “dreamer who dreamt the world”!); Stephen Dewey’s “Gather: Children of the Evertree” (deeply elegant conversational mechanics and diegetic teaching of the rules), Tim Hutching’s “Operation Linebacker” (a script made of real Vietnam cockpit recordings that shockingly subverted our expectations).

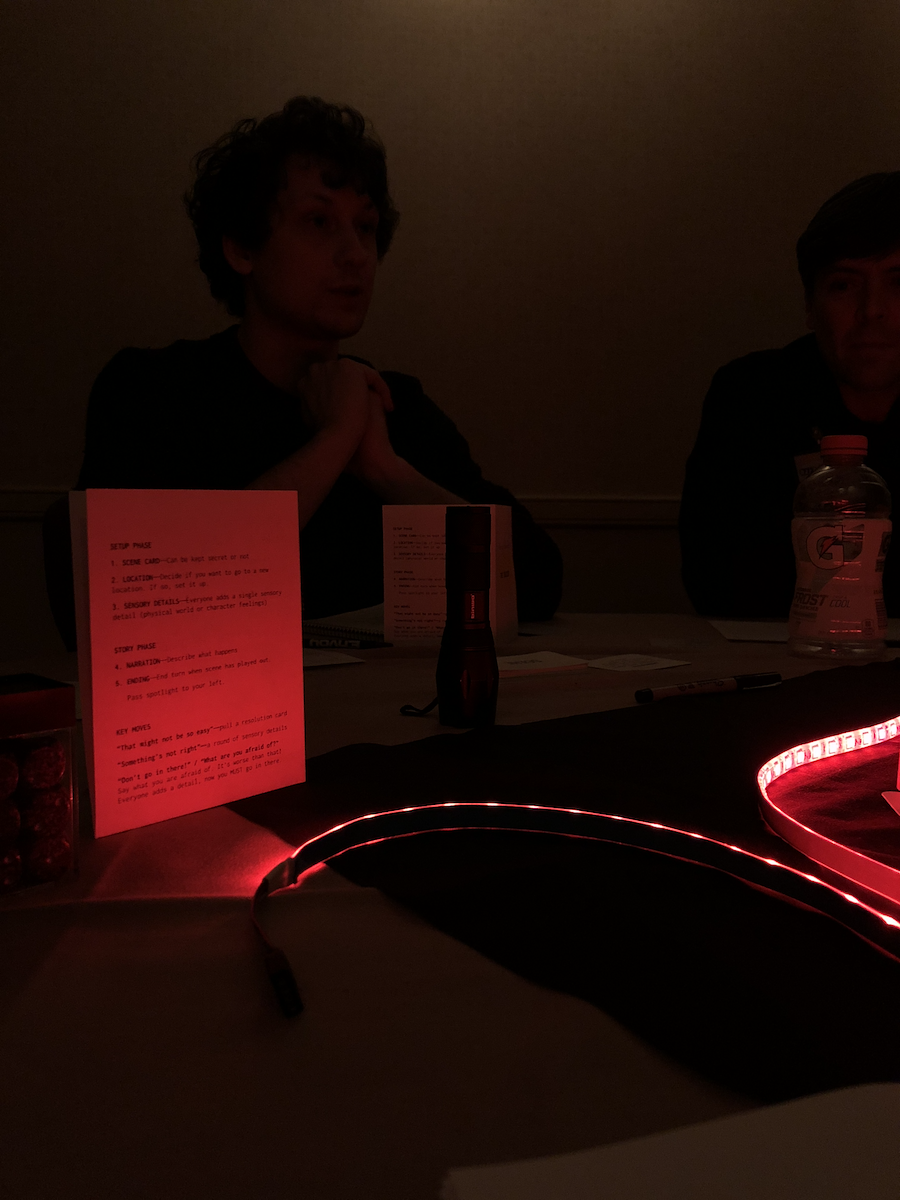

Thank you Avie & Vinny for an amazing time, and—what a segue!—for getting me the perfect space for three playtests of THE ZONE. It doesn’t look like much… but it was beige perfection. Oh “Headquarters B”, I will never forget thee.

And most of all thank you so so so much to playtesters Anne, Whitney, Allen, Robin, Elias, Brian, Eleanor, Sean, Korey (x2!), Michael, Jenna, Mike, Nina! Your feedback was an amazing gift and your stories were perfectly, teeth-clenchingly, shiver-my-spinefully, delightfully… horrifying. Squeeeee.

What did I learn?

I had hoped to test out player death mechanics (a crucial part THE ZONE and why the “Director” role is about scene instead of character control)—how it felt to have your character die, and whether it had the desired escalation as players shifted roles from embodying characters to being THE ZONE.

Instead, I found myself focusing almost entirely on the instructional design of the game.

The game doesn’t start when it starts

There’s an adjacent framework from the terrifying world of gnarly startup growth tactics called Psych’d, that puts this rather well:

- Every element

on the pagein the instruction adds or subtracts emotional energy- Inspiring

usersplayers is as important as reducing friction

Or to put it differently, how might I avoid this?

Explanation Of Board Game Rules Peppered With Reassurances That It Will Be Fun https://t.co/OiZwLlOKxj pic.twitter.com/GGsqFh7F97

— The Onion (@TheOnion) November 4, 2018

How might I maximize the emotional energy of my players during the necessary 30ish minutes of instruction? And which parts of the instruction actually correlate with a better game?

My first playtest was a perfect stress test: people were sleepless, stressed from prepping their own games for playtests. By the end of my rambly intro, the energy level was gone. We’d spent far too long discussing safety mechanics, trying to internalize rules out of context, and my decision to skip character creation saved time but left people without skin in the game.

A humbling start!

Just before that playtest I’d attended a great panel on horror, moderated by Anne Ratchat, in which an audience member paraphrased the genre as: giving players interesting bad choices”. I had a realization: I had to give players stronger incentives to define their character’s psyches, then create explicit reasons to express their character’s fears out loud so other players could learn and act on them. I want THE ZONE to be an engine for defining and playing with the two sided coin of fear & temptation. Every mechanic should make players complicit in ratcheting both up mercilessly.

(And yes, fear and temptation—horror & love—flipsides of a same coin. Horror isn’t just about removing agency. It can be about getting exactly what you want… at the wrong time.)

I had to focus on the singular goal of the game: to help players safely explore themes of horror and loss of humanity. The entire game world, the intro to the game, and every part of the instruction of the rules should help set the tone. Even the microcopy on the character sheets and the sample Phobias & Temptations were a surprisingly important part of this world building.

In the second playtest, I completely changed the sequencing. A short storyful intro to the world, then character creation. I used the Phobia part of the character creation as a jumping off point for safety mechanics, which worked well, then taught the 3 key moves in a set of short workshopped scenes. 40 minutes! Too long, but it mostly worked. People felt more invested and excited having just created rich characters.

The third playtest was much better. I got a wonderful piece of feedback to take the time not just to level set on safety—what people wanted to avoid—but to also to explicitly discuss what people wanted. I learned a cool thing from a game called Annalise where players are encouraged to explicitly write down on an index card when a cool theme is introduced, so that everyone remembers to build on it.

The world exists to define & amplify the characters

This video essay about Guillermo Del Toro’s monster design sums it up well: the world that gets created around the monsters—or in this case the players—should exist to mirror, amplify, and twist the knife in their deepest fears. THE ZONE doesn’t exist for pure world building—it’s a foil to the characters.

Very excited for where the game has ended up after Metatopia. My next playtest will be an explicit test of the refined rules and instructional design. My goal: to be able to hand players the materials and have them up and running with only limited influence from me.

Can’t wait until Metatopia 2019!

Epilogue: how to cram a 3 hour game into 90 minutes

- Skip character creation… but only if it’s not integral to empathy in the game. In THE ZONE, you really need it. On the other hand, it did no harm to skip the location setup

- It didn’t matter that we didn’t get to the ending. In fact, ending halfway created a rather nice cliffhanger

- You can shorten the story by switching the depth of the scene. It worked very well to have players do quick epilogues for their characters. The hierarchy here would be LARP —> Acting out conversations —> Rich descriptions with everyone involved —> One player just tells the story —> Quick summary. Nice way to still get to the ending

- Safety is the one thing that I’d never skip, but you can certainly shrink it down, particularly as players will have heard it in a bunch of other games

- It will start 5-10 mins late. Decide on a start time and stick to it

- Don’t rush feedback. Ending with a full 30 minutes to go was about right, with an extra 5 minutes of buffer to give people time to get to their next game

- Know what you want to test! If players are stuck in an area you’re not trying to test, it’s OK to course correct and move things along

- Feedback forms were great! Give them out at the beginning, with pens, so people can jot notes as they go