Last weekend I had a chance to play my game “They Say You Should Talk To Your Plants” (heretofore referred to as Planttalker), with a wonderful group of fellow larpers. (This is surprisingly rare, by the way; many Golden Cobra games are developed in such a mad experimental rush to hit the contest deadline that they are rarely playtested—mine certainly wasn’t!)

So it was a real gift to get a chance to jump in. And it made me want to talk about one of my favorite concepts in the world, the Group Mind.

The structure of Planttalker

Planttalker is about a protagonist going through life, in all its ups and downs. Life gets, well, lifey. Some good happens. Some bad. And through it all, a group of players take turns embodying this one very human human, while also playing their very planty plants. The human keeps the plants alive. The plants pull emotion and truth out of the human.

(By the way: the game is here if you want to read it first—it’s short and sweet)

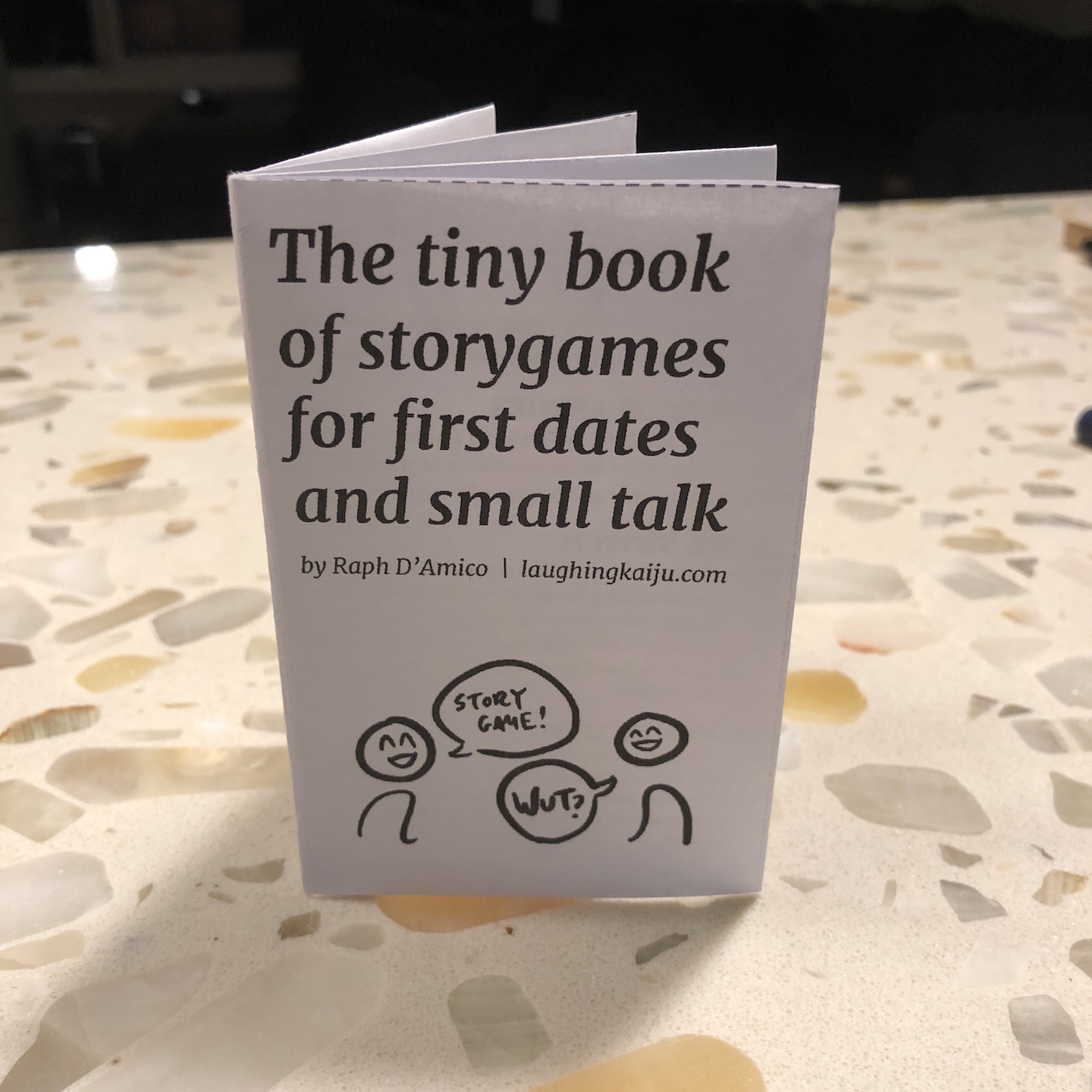

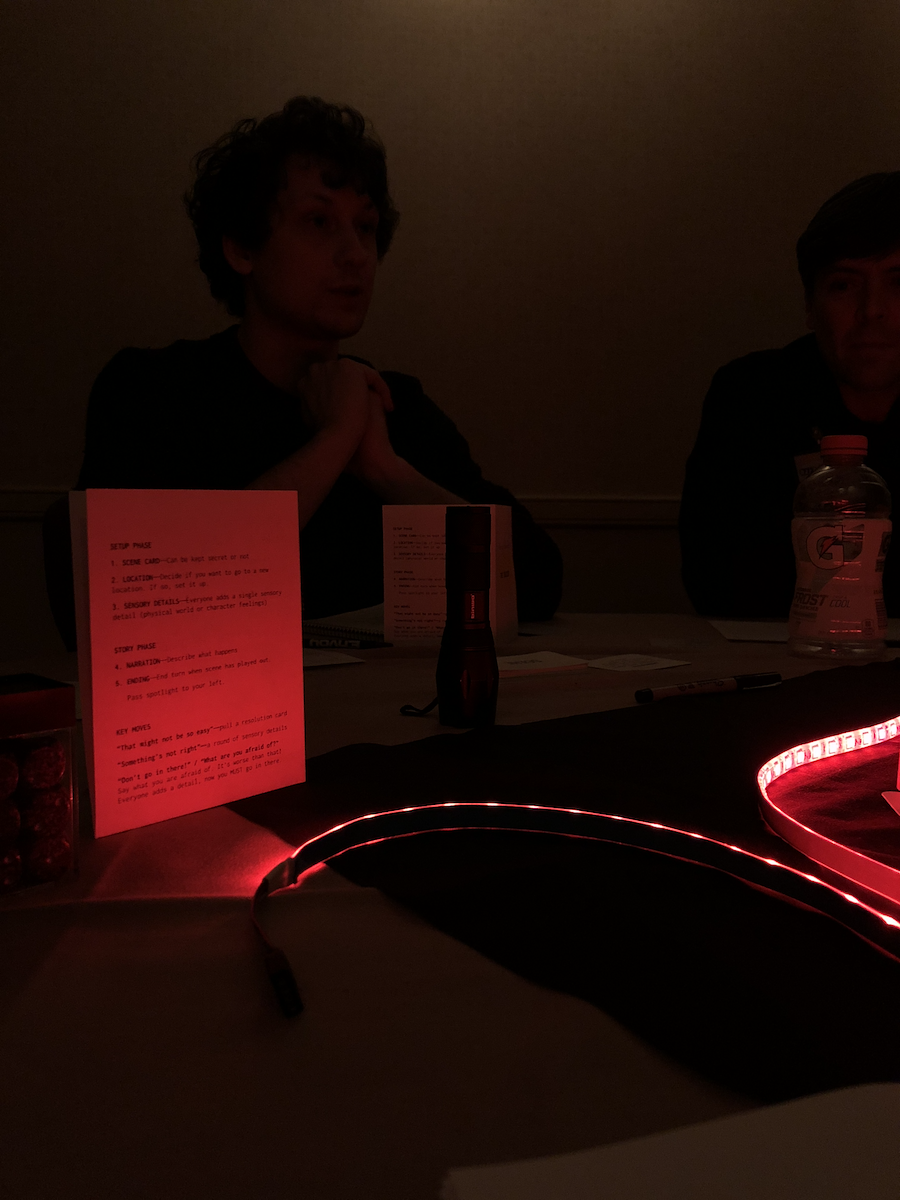

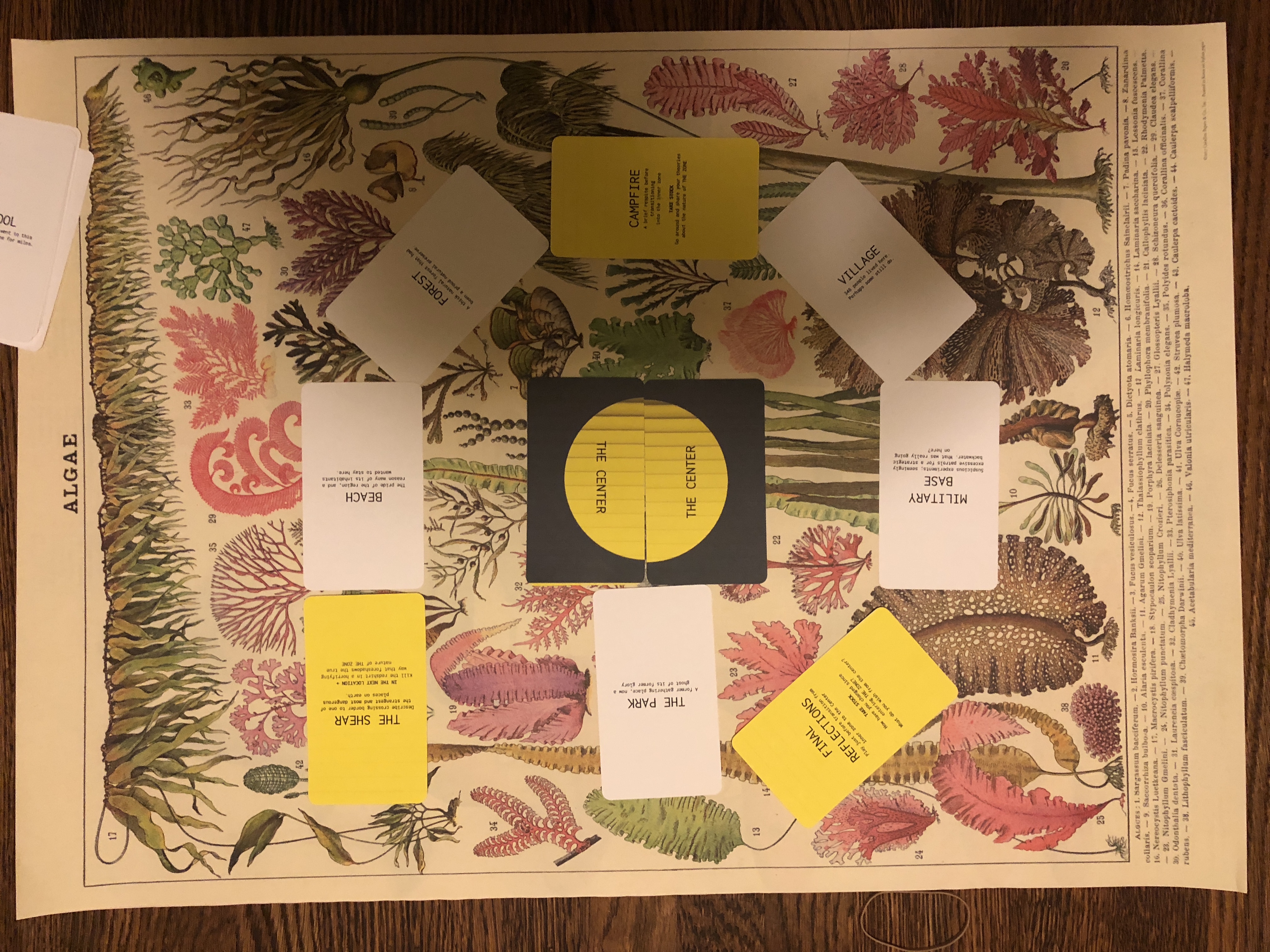

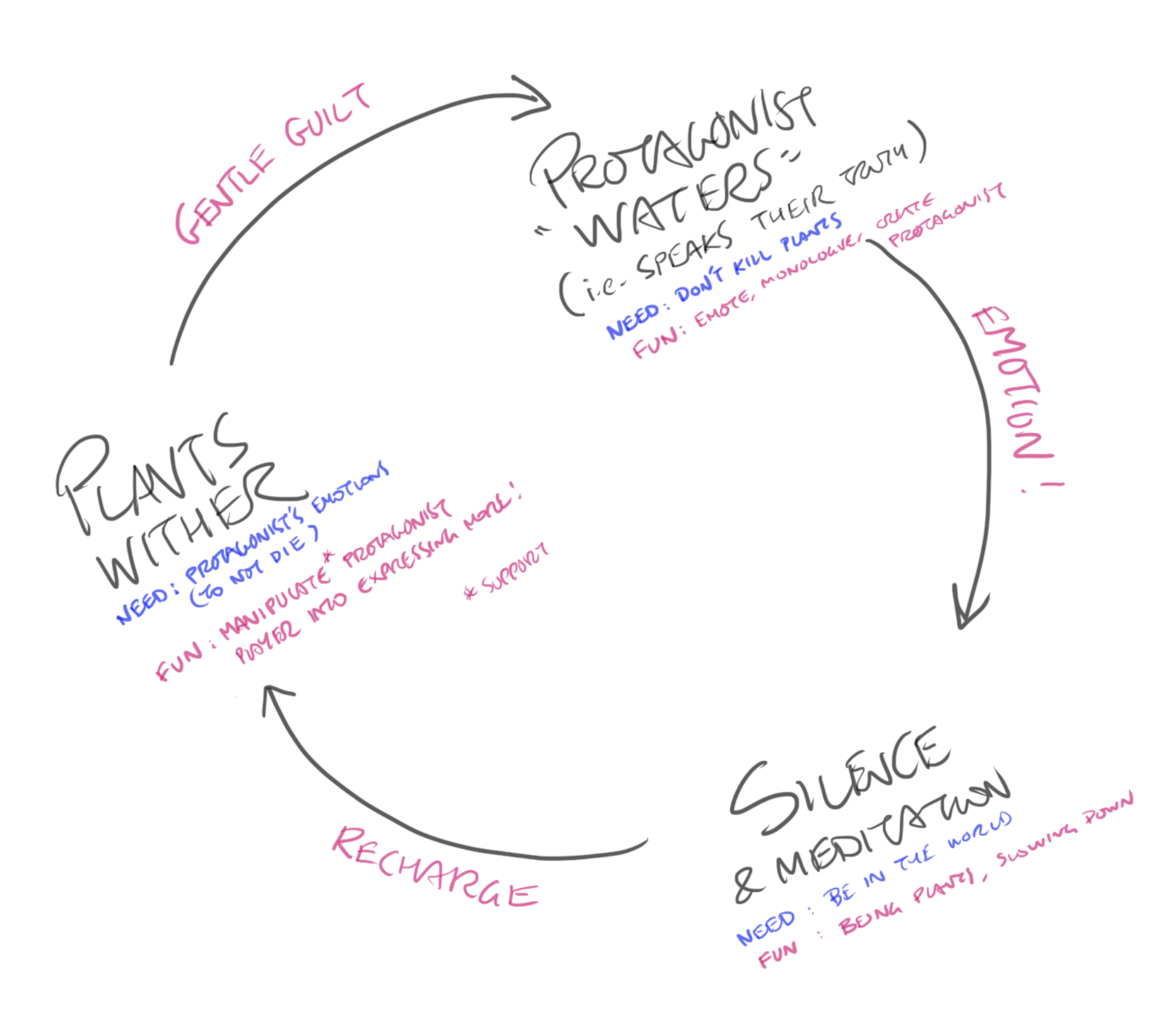

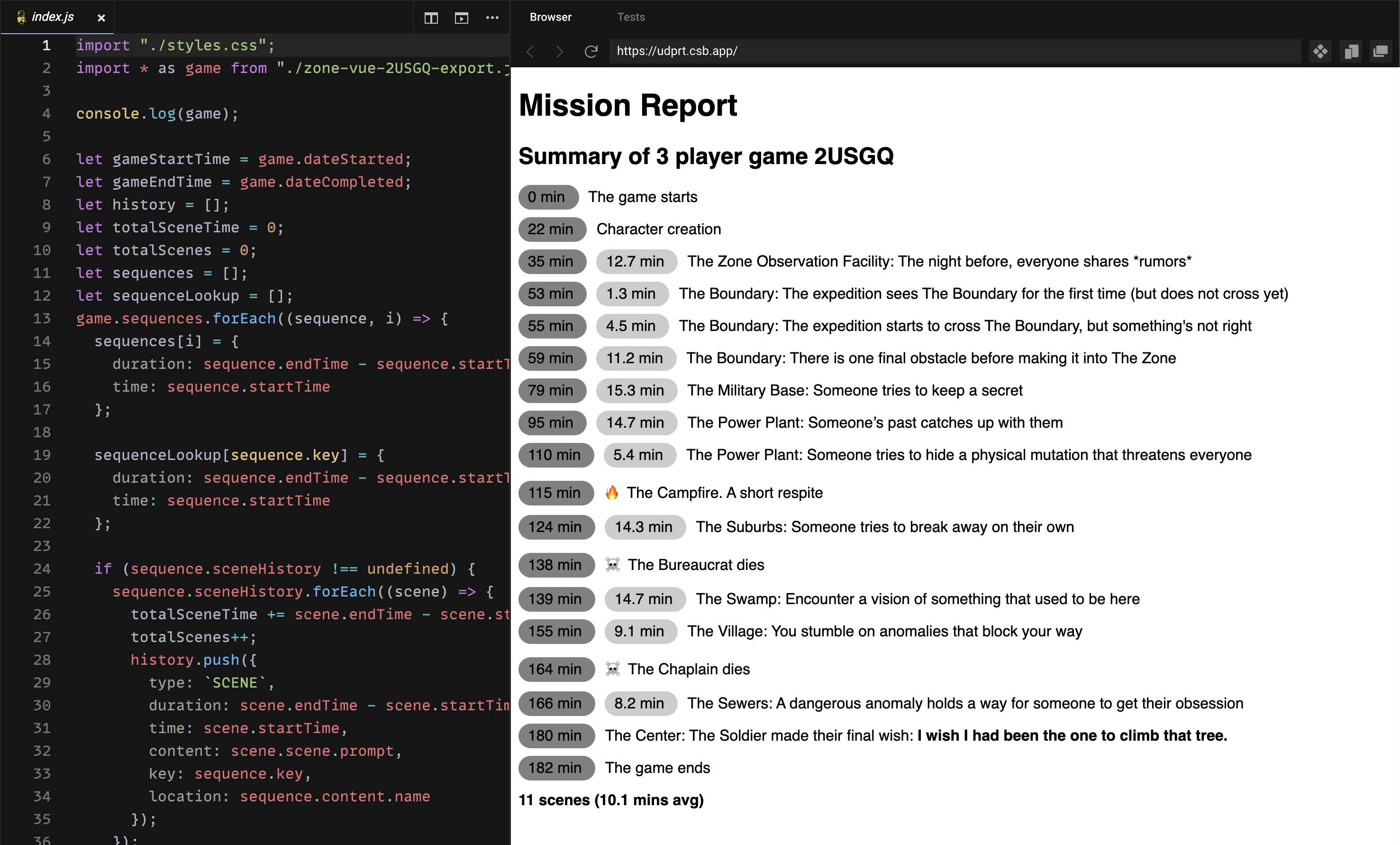

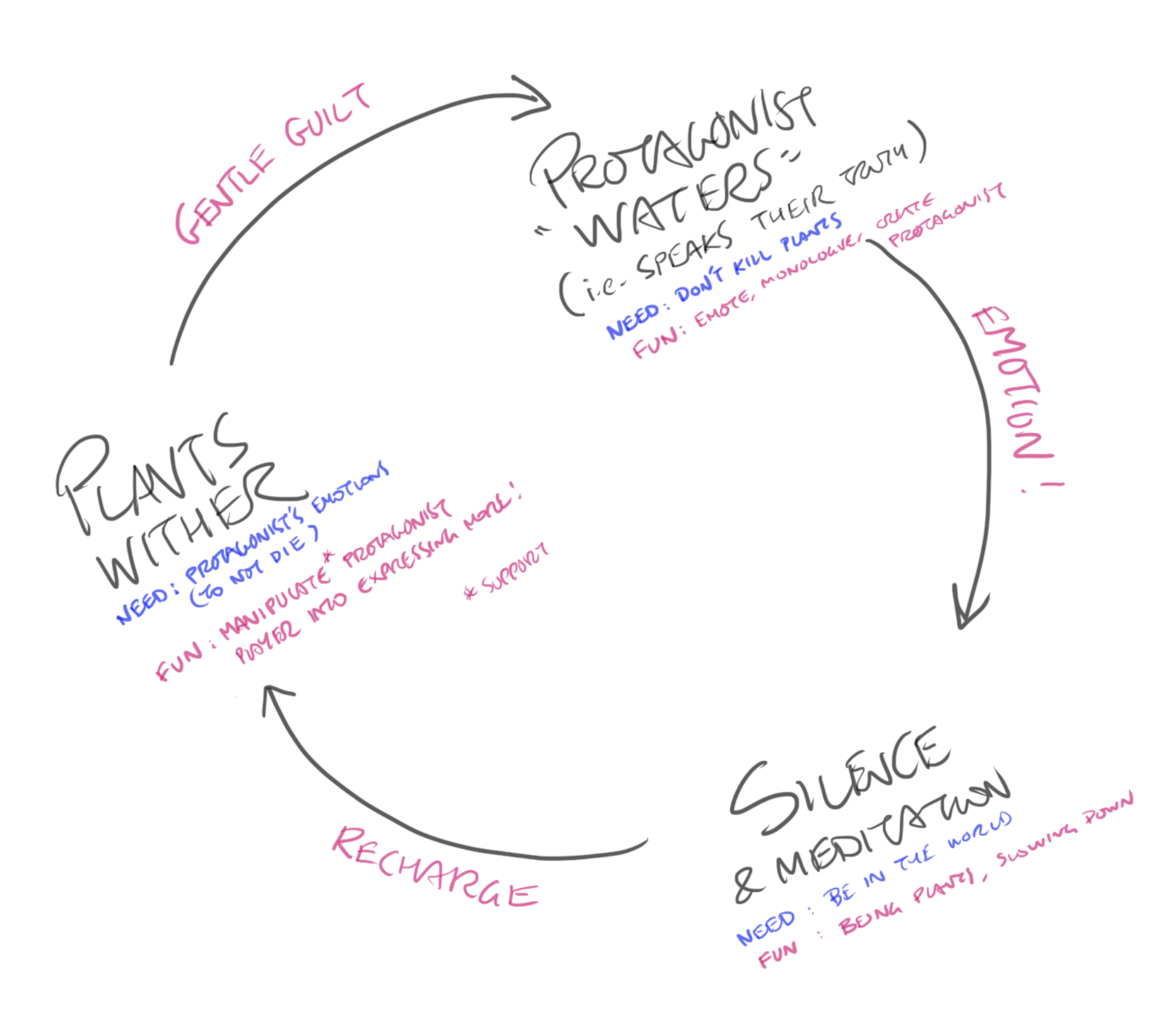

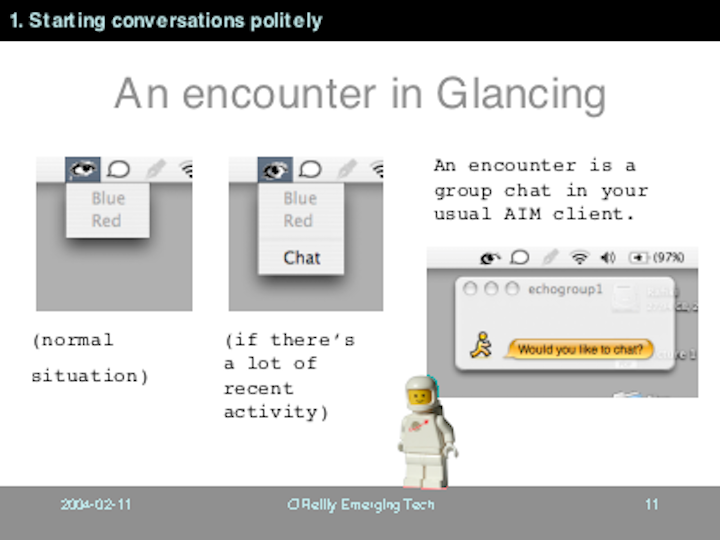

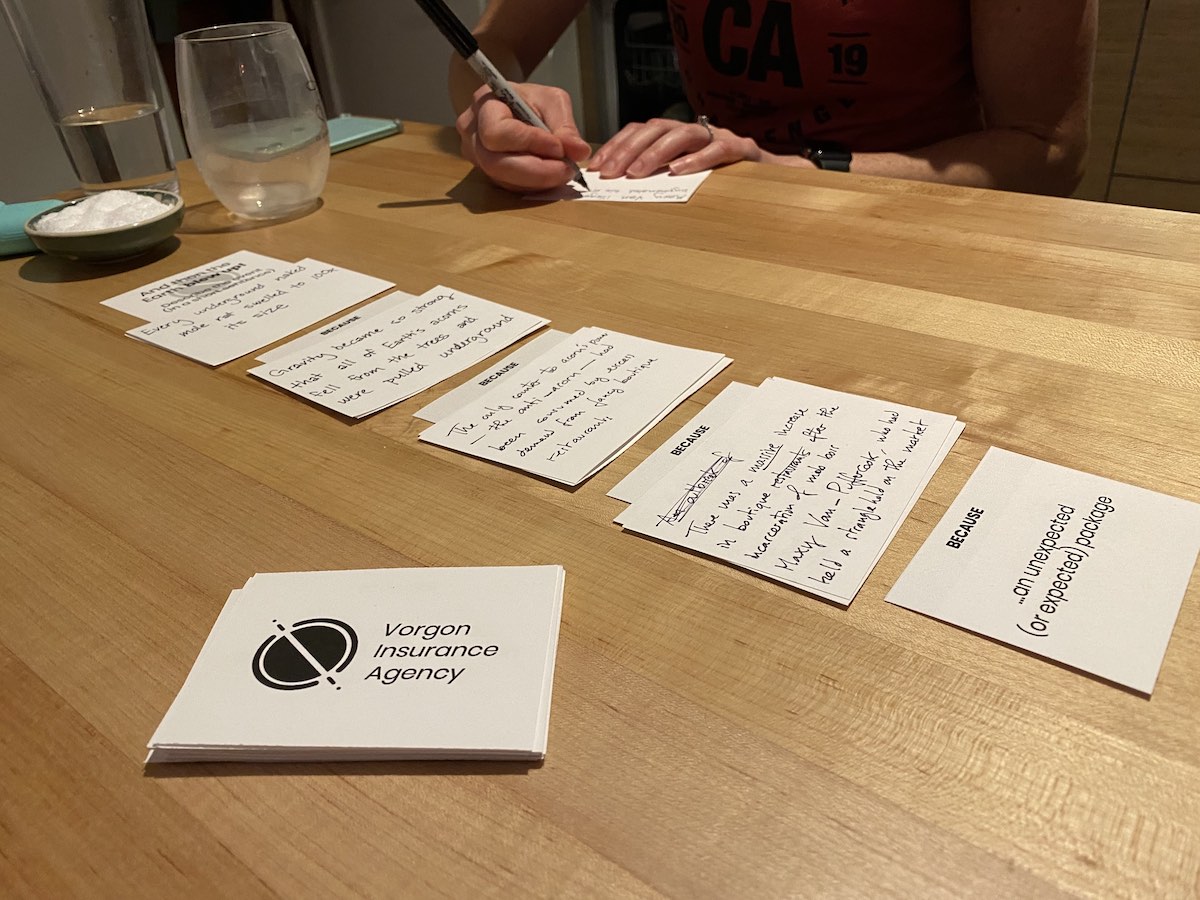

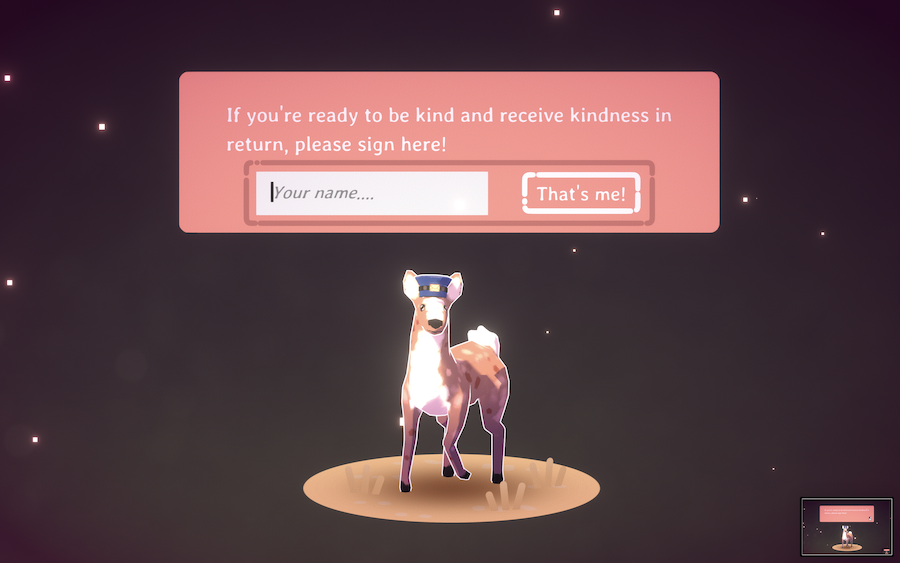

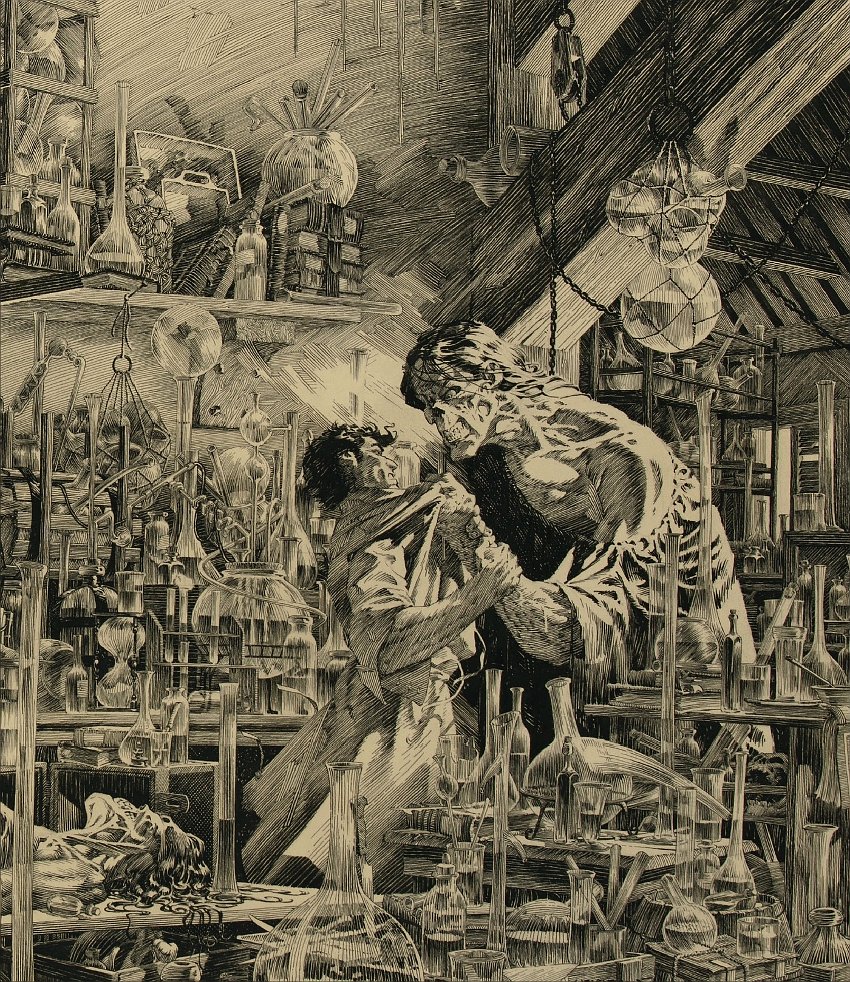

This is what the game looks like:

In our story, we manifested Alex, a young 20-something who’d just moved to San Francisco from his small Southern California home town, to start a new job. Soon he was in his first serious relationship, which thrilled him—though not his plants—until it ended a year later. His job became a slog. Depression took him. He was laid off, and moved across the country only to end up working remotely out of his apartment, doubly lonely. Seeking love, he found companionship instead in fostering animals.

In a memorable scene, Alex clings to the still raw organizational tricks he’s learned to avoid falling into total squalor, and is excitedly talking to his parents about Stella. At first we think he’s met The One, but Stella is actually a beautiful golden retriever he’s about to adopt. In the next, the adoption has fallen through. Dejected, he turns to his plants. At least they are there for him.

Begonia hands him a card that prompts him to remember a time in the past where he truly felt Worthy. He remembers a moment of true non-judgement away from his parents, at a summer camp where he could be completely himself.

In the final scene he’s back in his hometown, a couple of decades passed since his mildewy first apartment where sun loving Succulent was in a dark corner while the family’s heirloom Swordfern’s back burned under the window. He’s grown. He is now an experienced foster dad. Centered. Imperfect.

A fully fledged person running like a simulation within our group mind.

And shockingly real, like a memory.

The group mind

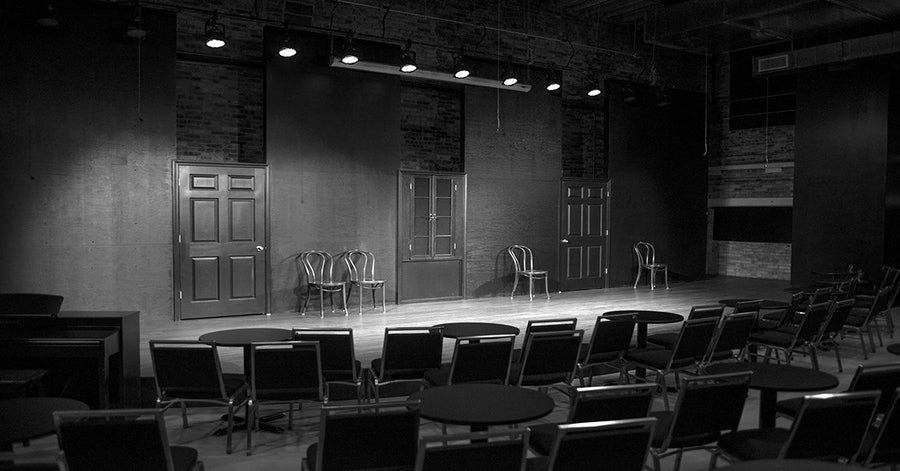

The group mind is a core concept in improv. It’s the shared understanding of the fictional reality created by the improvisers on stage. It’s a shorthand for a feeling: of losing yourself in the shared reality, letting your individual identity take a walk while your consciousness manifests whatever the scene needs it to.

Karen Twelves, in her must-read-if-you-are-a-gamer-book “Improv For Gamers”, defines it as:

“The moment when improvisers are so keyed in to the same idea, the scene falls perfectly into place”

And oh do I love this quote by TJ Jagodowsky, one half of legendary improv duo TJ & Dave, from their book “Improvisation at the Speed of Life”:

TJ: “It’s a bit like there is a song that is always playing or there’s a poem that’s always being read, but when that extra thing happens—when Harold visits—you hear it. For this little bit of time, you’re so connected to another person or a group of people that you’re able to hear this music that’s always there just beyond your sense and it seems to help determine what it is that you’re supposed to do next. And now everyone is hearing it”

Beautiful ❤️

Pam: Have you ever felt that way off stage?

Dave: Not that I recall … not without psychedelics

TJ: I think the closest that I feel is either being in love or something in nature where, again, you’re like a participant but you’re also an observer. And it’s something big.

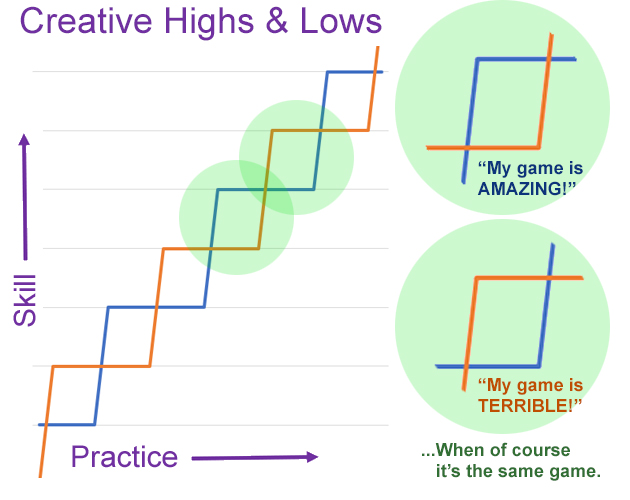

Group mind can be strong, or it can be weak. A team has strong group mind if they are clearly inhabiting the shared world as they create it, listening and actively making micro-adjustments whenever confusion arises. Weak group mind looks like a bunch of individuals trying to push and pull it in their direction, “writing the scene in their head” instead of letting go of anything that hasn’t been expressed.

In improv, there is no time. Anything that’s in your head doesn’t exist!

Group mind matters because it so obviously applies to every domain of life—to a business meeting, a brainstorm, a relationship (think of that couple you know who can magically read each other’s minds to leave a party at the ideal time). On a macro level, the epic challenges facing humanity right now demand that we find a way to achieve group mind at the scale of billions.

Side note—“group mind” is sometimes confused with “groupthink”, but they could not be more different. Groupthink is a dynamic where valuable individual thinking is suppressed by a culture that implicitly or explicitly punishes dissent. Group mind, on the other hand, is when a group of people is so in tune to each other’s contributions that they accept and build on each other’s contributions without judgement. It seems subtle, but the difference is huge: with “group mind”, individual contributions aren’t devalued, bur rather immediately celebrated into the shared reality.

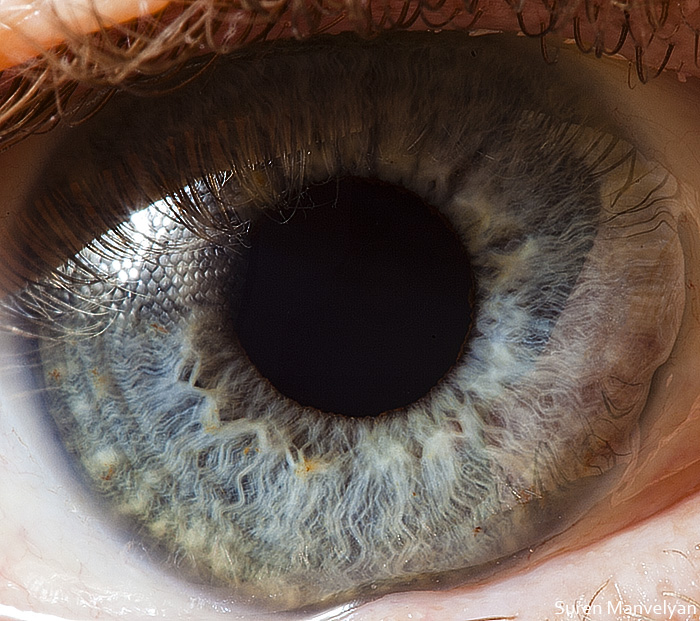

So what is the group mind made up of?

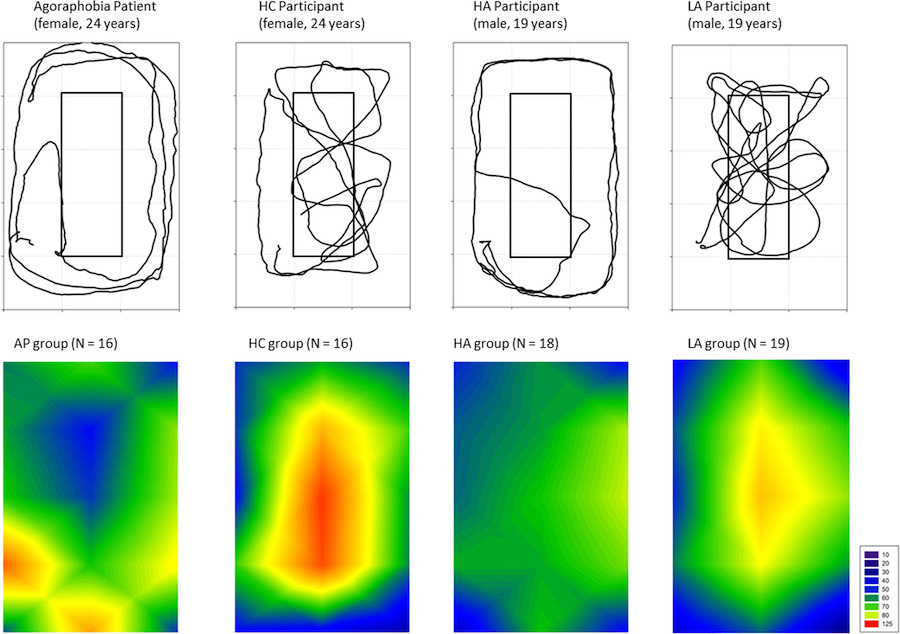

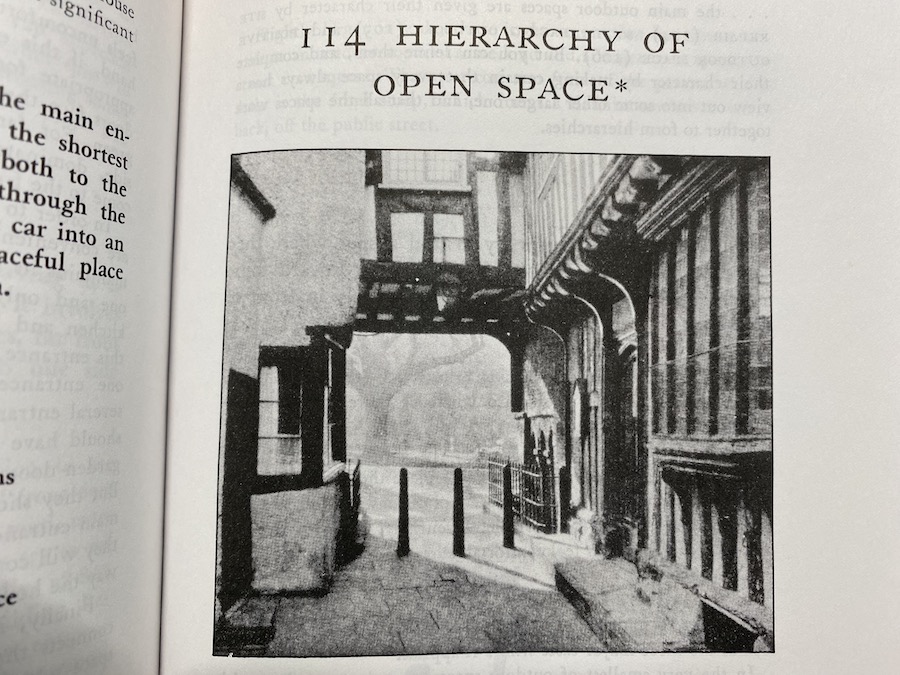

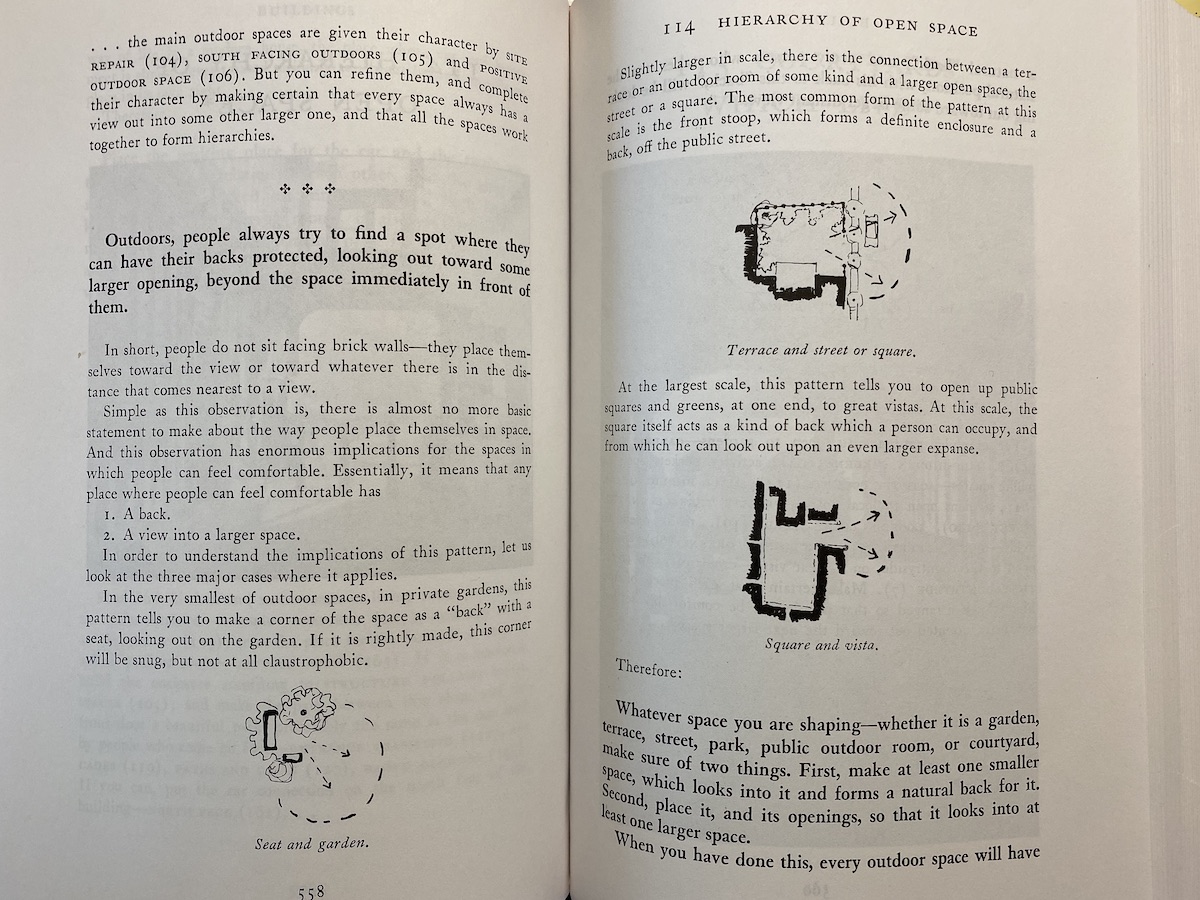

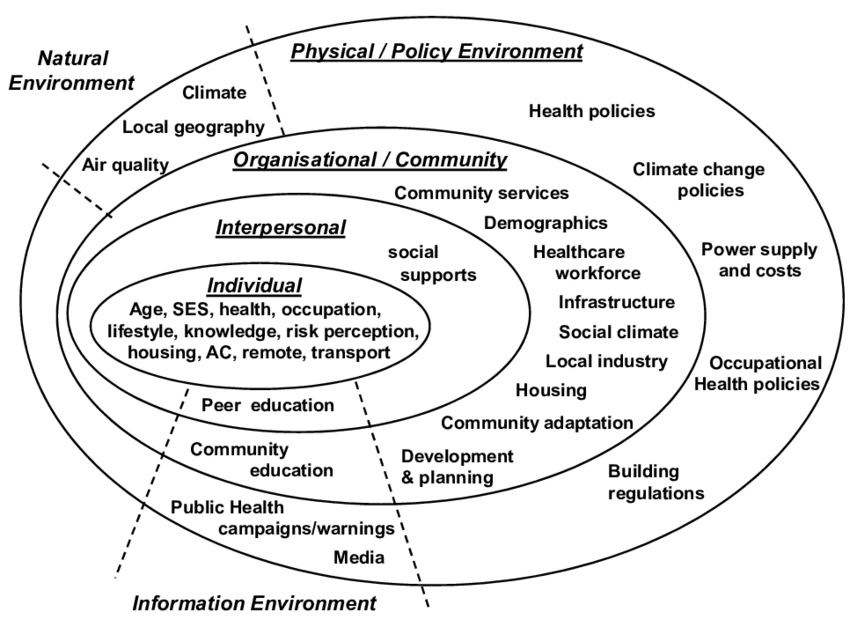

There is a procedural approach to thinking about the group mind which I find terribly compelling. It starts with individual psychosocial mechanics, like “Yes, and” and the subtle interpersonal cues that Sandy Pentland calls “honest signals”, such as mirroring, rapid back and forth, consistency of speech, and physical excitation. Much like Christopher Alexander’s pattern language of physical space, these are the patterns of individual behavior that lead to people interacting more fluently.

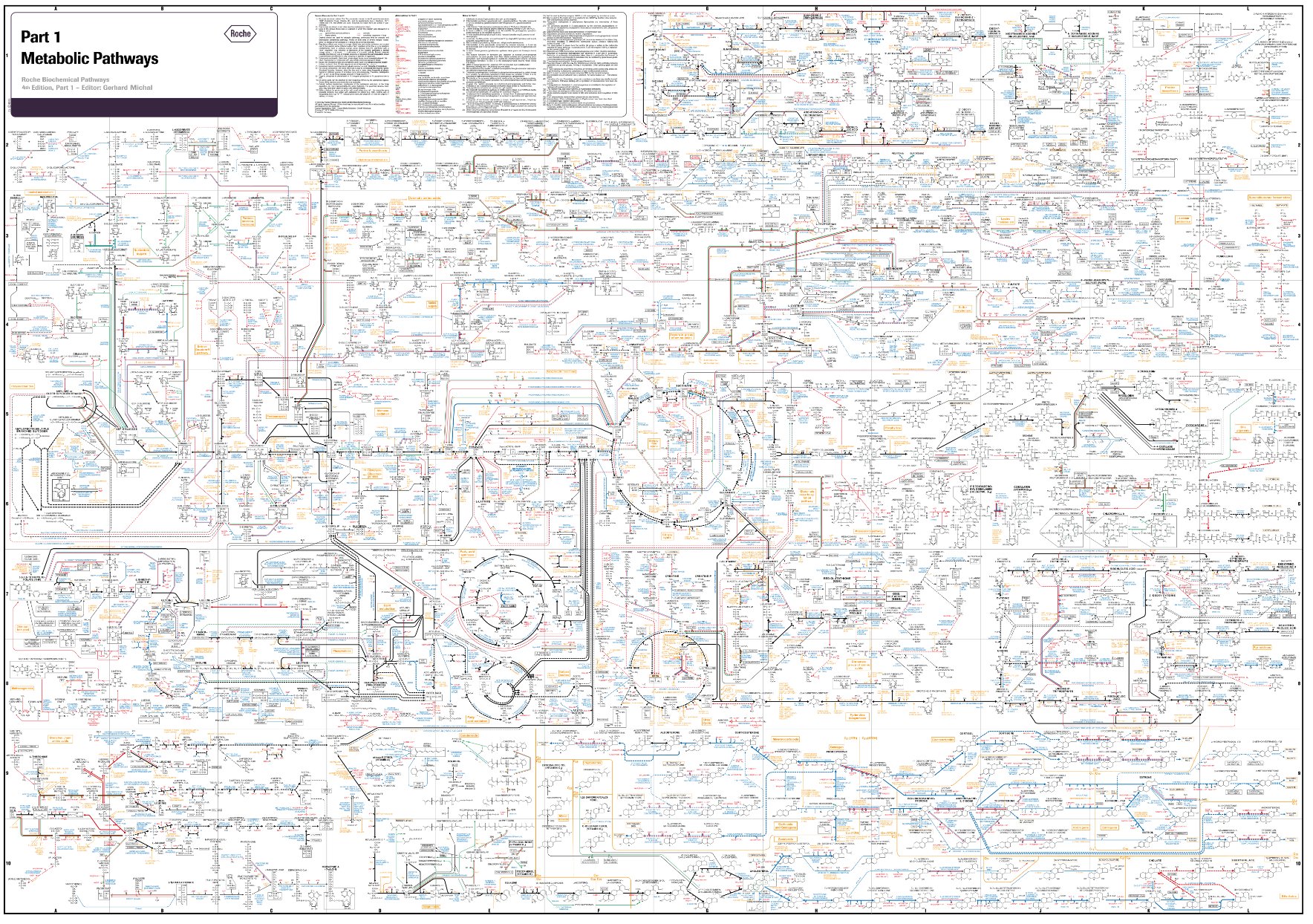

In this metaphor, the gaps between people are synapses and any communication that bridges those gaps (body, voice, visual, writing, Figma) are the neurotransmitters. The “group mind” is the emergent intelligence that arises out of this conversation, a distributed computer similar to the collective intelligence of a beehive. The goal is to increase the bandwidth of this communication, and remove distractions. (Get your phone off the table!)

So if you want to tweak the group mind, you can look at the “neurotransmitters” available and seek to increase the bandwidth.

Aside—I think the difference between the shared reality of a classic, idealized “two pizza team” and the Dunbar number is exactly about this—the small team not only can share a collective hallucination, they have enough information to know what the others in the hallucination are experiencing and, if necessary, take action to correct it. Hundreds or millions of people can share a collective ideology, but more of a broadcast than a direct back and forth.

But all of this is table stakes. Increasing the bandwidth isn’t enough—you have to sequence it right. Focusing just on the the “amount” of communication is like saying that composing music is about the “amount” of notes. Sequencing, tempo, arrangement, is what makes the melody.

You also have to look at the organization of the connections—easy and egalitarian if it’s six people on an improv stage, much more complex as power dynamics come into play or the number of people increases. (As Kim Erwin, my communication design professor at the Institute of Design, used to say: “Politics is whenever you have two people in a room”)

A simple example of second order mechanics

Now here’s the juicy stuff. My favorite simple example is in Cass Sunstein’s book “Wiser”, a compendium of ways groups get in their own way.

Imagine that you have a dozen people in a meeting trying to make a crucial decision—blow up Alderaan or not? The question is complicated. Will it galvanize the resistance? Or firmly establish the Empire’s authority? Most of the people in the meeting are wavering, but are generally against the plan.

But (Grand Moff) Jeff speaks first, and even though he is only barely in favor, speaks eloquently and comes across as quite certain to the others. Audrey is next, and although her own data suggests that this might be a bad idea, she trusts Jeff. She decides to go along with it.

And now we get to Davis. He also thinks this might be a bad idea, but he now he has two colleagues who want to do it! He trusts them—they must know something he doesn’t. He says “Aye”, and now the cascade is unstoppable. Even though they were all doubtful at the start, they end up all voting to power up the Superlaser.

And here Sunstein makes a crucial point:

“In the real world, many group members do not consider the possibility that earlier speakers deferred to the views of still earlier ones. People tend to think that if two or more other people believe in something, each has arrived at that belief independently. This is an error, but a lot of us make it”

Had a different person spoken first, Alderaan might have survived—but what matters even more is our distorted perception the first two.

Reminds me of the importance of the second dancing guy.

We make our judgements not just based on our own opinion but also based on what we perceive other’s opinions to be. Why? Because our tiny brains can only perceive a fraction of the complexity of existence, so we’re socially wired to use the collective intelligence of our trusted peers as good proxies. This makes sense!

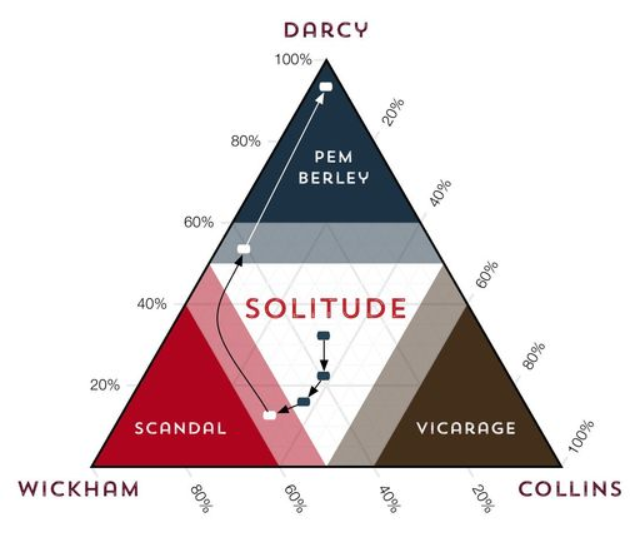

How do you avoid that? Sunstein’s book has eight approaches, one of which is the “Delphi method”, a simple tool where you vote at the start to reveal people’s preferences, deliberate, and then vote again at the end. It’s a simple and powerful system.

My favorite low-key version of it to implement is to have people close their eyes, stick out their fists, and do a thumbs up or thumbs down—or something in between. Everyone opens their eyes simultaneously and gets a clear sense of the starting state.

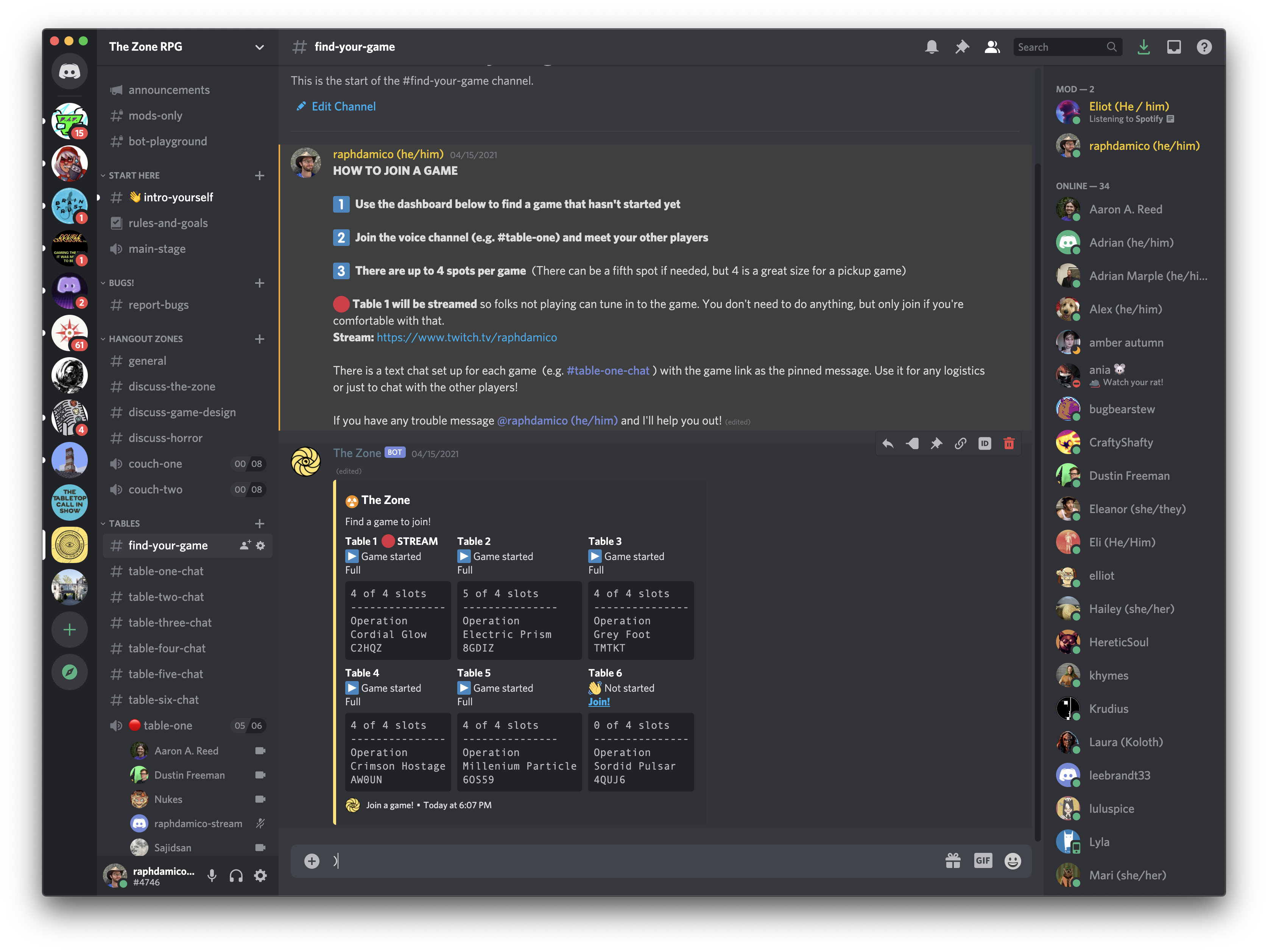

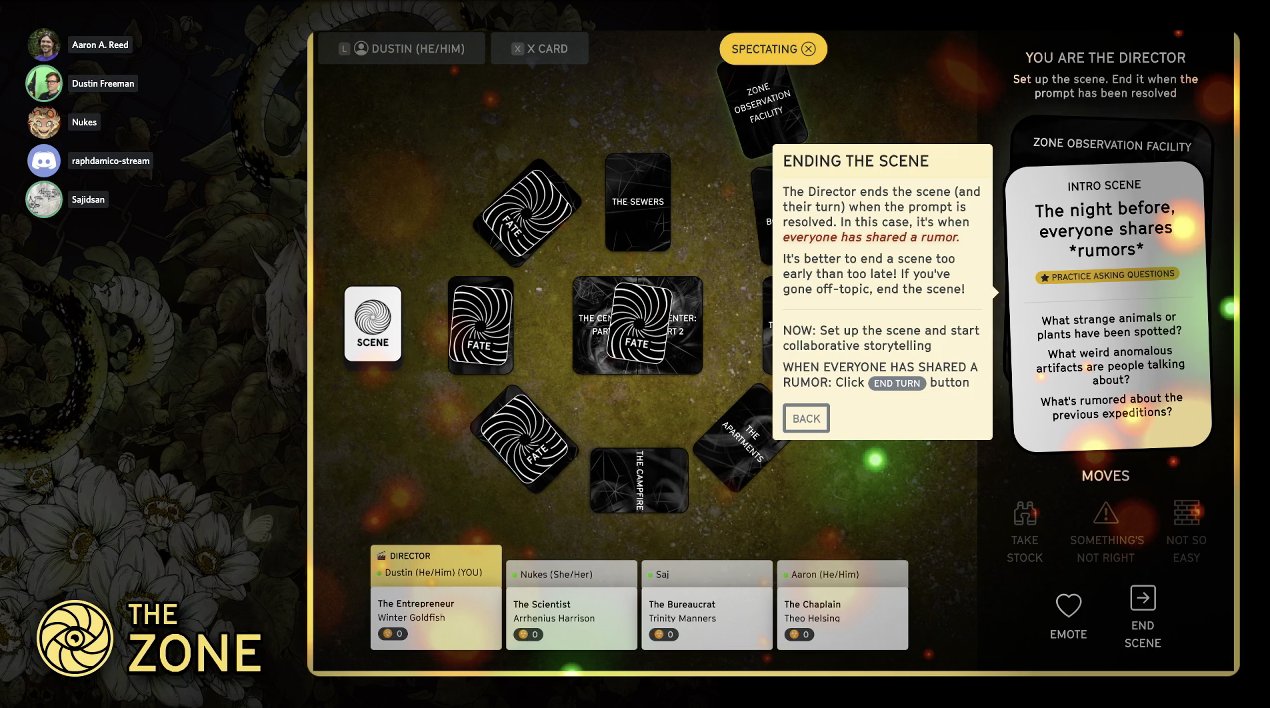

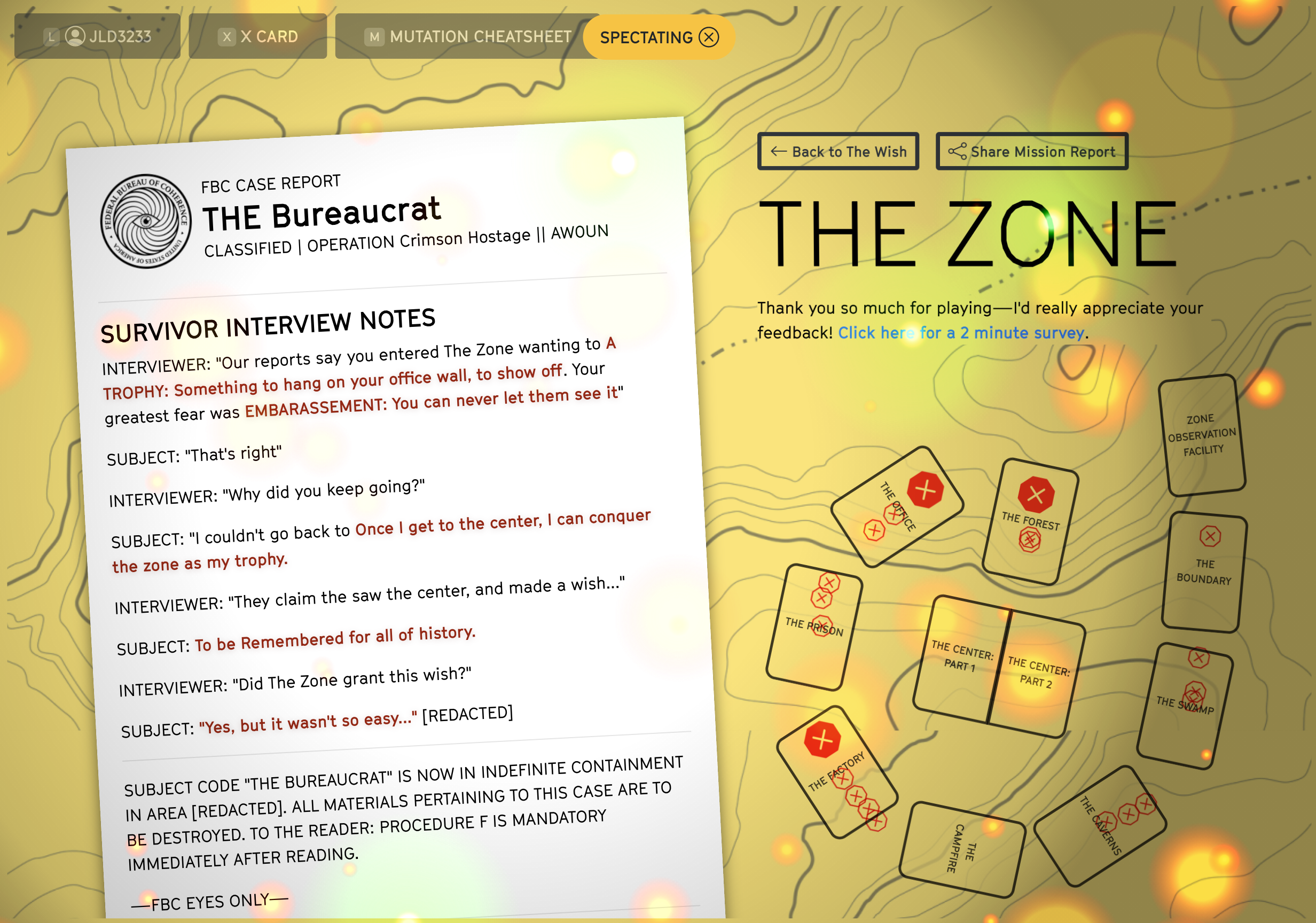

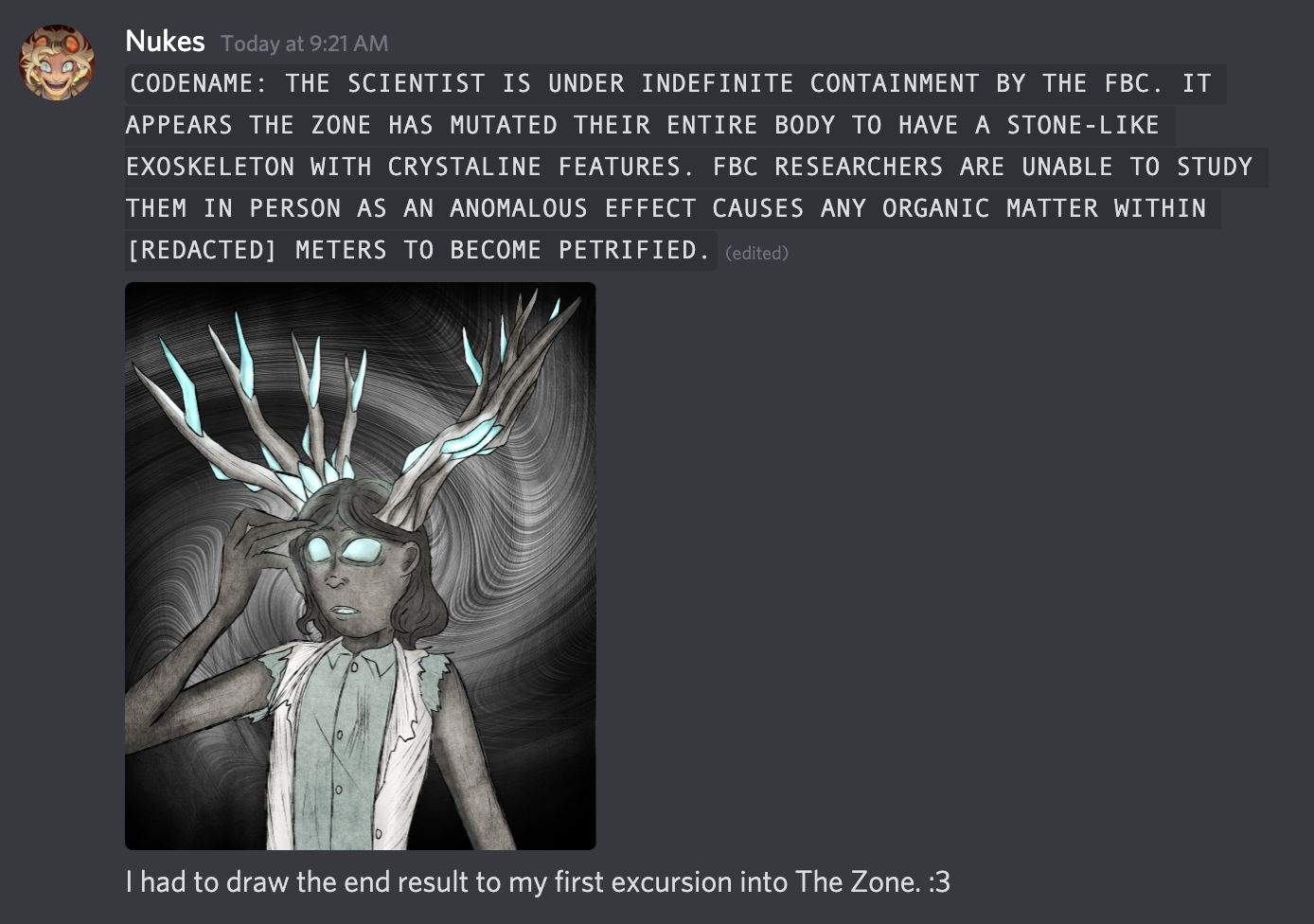

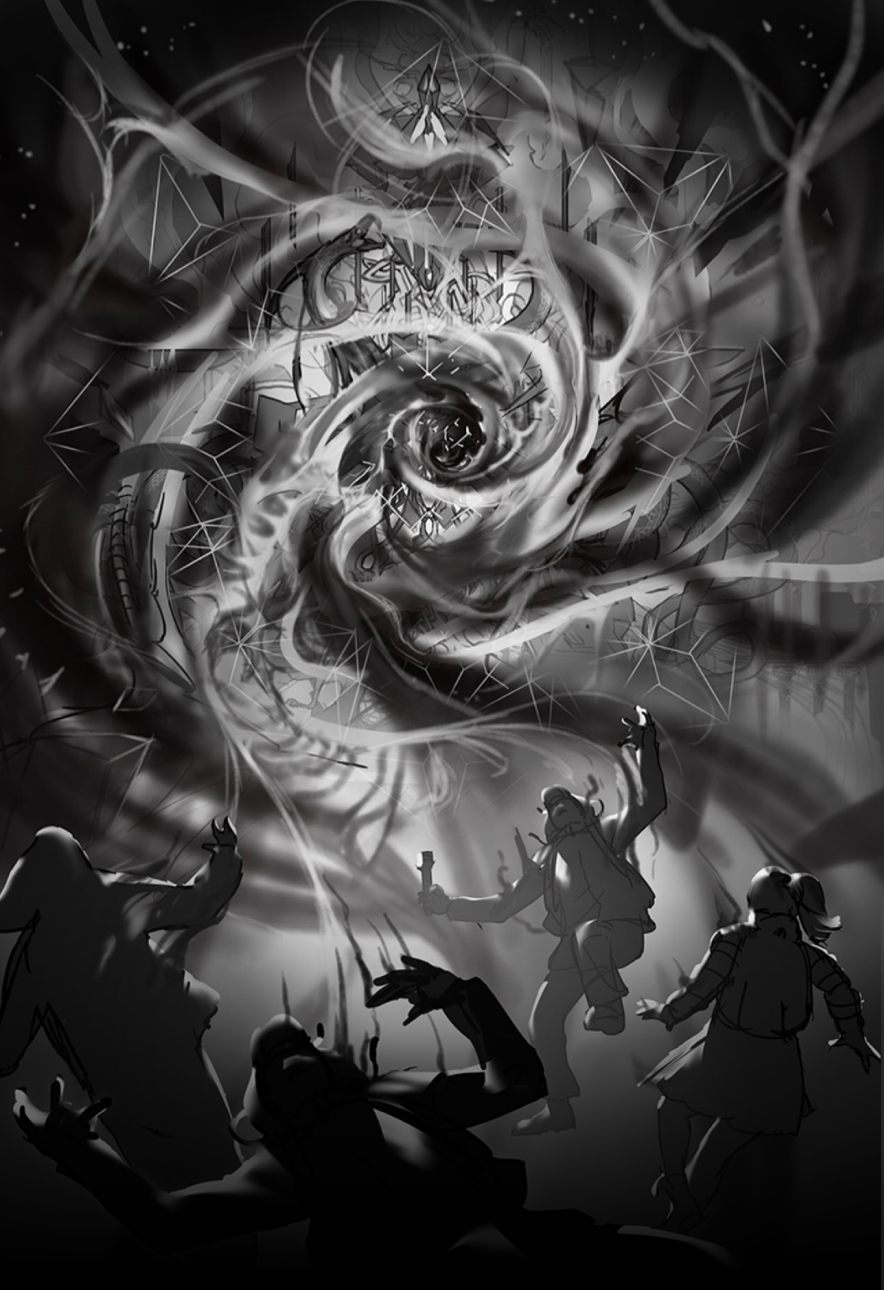

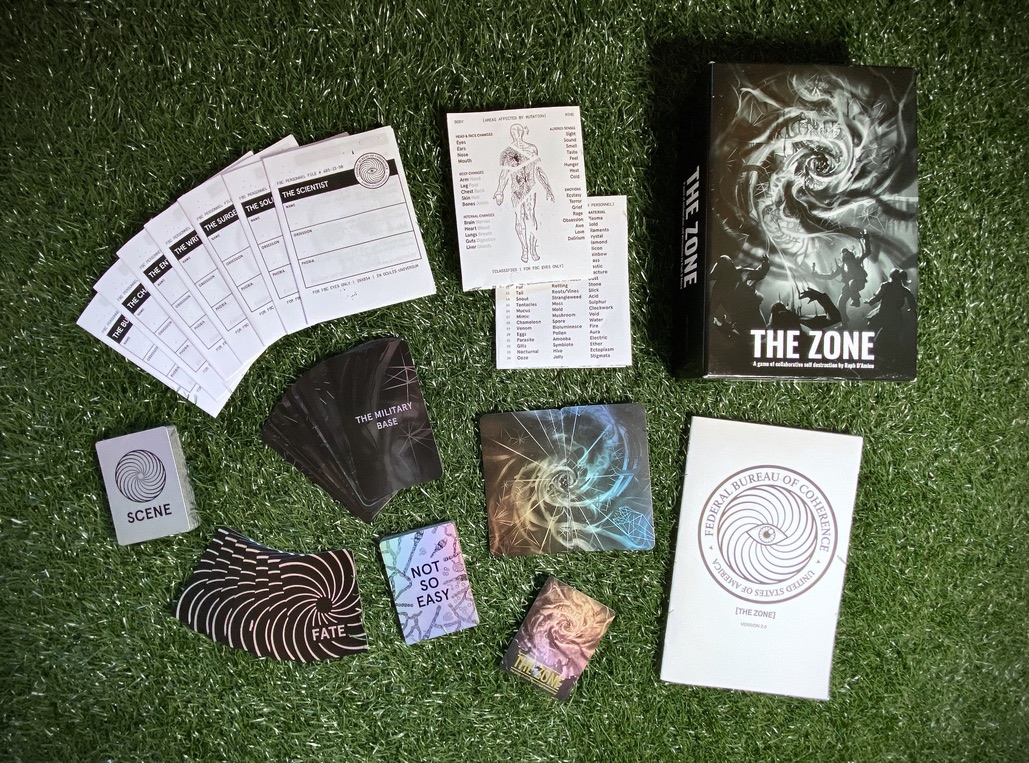

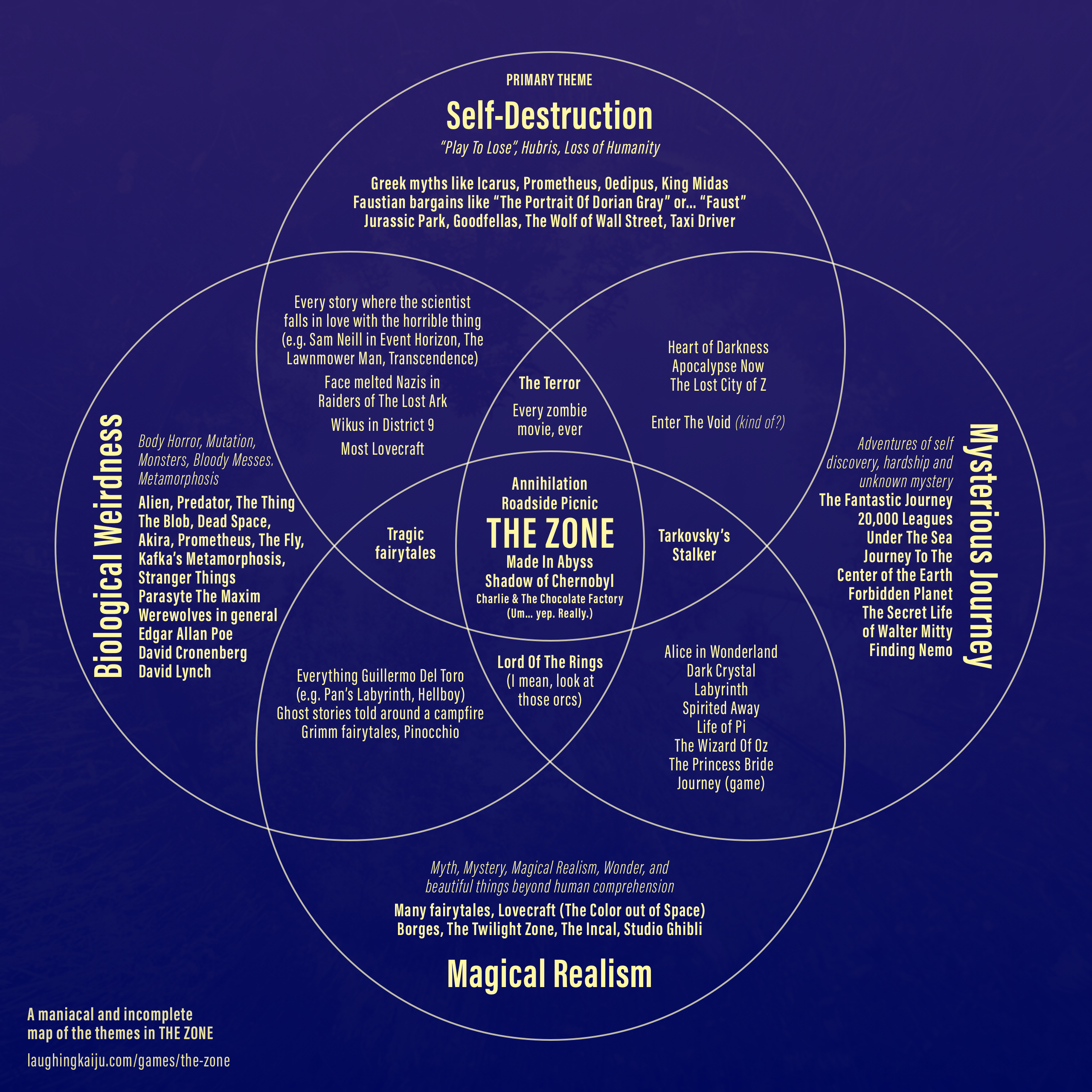

I use a variant of this to level set on the level of gore and horror in The Zone—full thumbs up is R-rated and thumbs down is PG-13—except here the Facilitator keeps their eyes open and sets the level of the game at whatever is the lowest comfort level. This way, if someone is slightly embarrassed about their desire for a less gory experience, they don’t have to out themselves.

Mechanics change how groups make reality

I wanted to talk about this fairly trivial example to highlight how simple mechanical changes—who talks first, whether there is an order to talking, how information is made public—can totally change the reality manifested by the group when they intersect with our cognitive biases.

And here’s where we get to game design. Roleplaying games are literally about manifesting new realities from scratch. There’s an intense magic to the moment the pieces start to come together, an overwhelming tidal wave of group mind when you realize that not only are you treating a fictional character as real, but everyone else is too.

It’s the gaming equivalent of one person in the middle of the street looking up at nothing, and quickly creating a traffic jam as everyone tries to see what’s up.

The beauty of GM-less games

Plant talker is a larp, but take out the acting, and it structurally belongs to a category of GM-less games (which is what most larps are). This means games where there is no all powerful “dungeon master”, “warden”, “games master” or “MC” who owns the world. There may be a player who manages the rules of the game, but the game itself is equally shared.

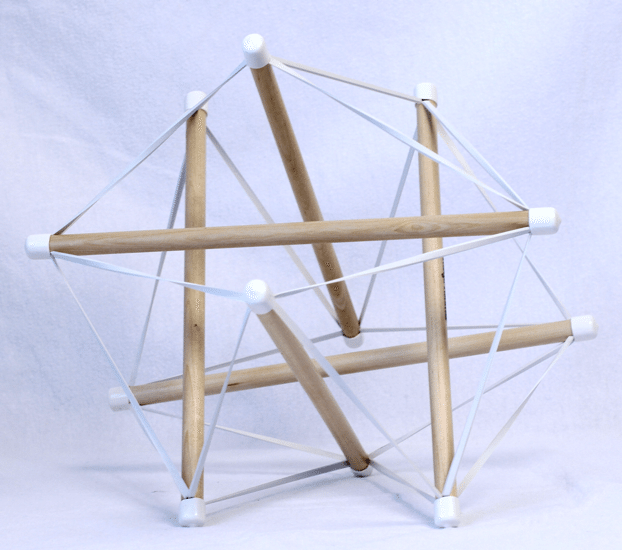

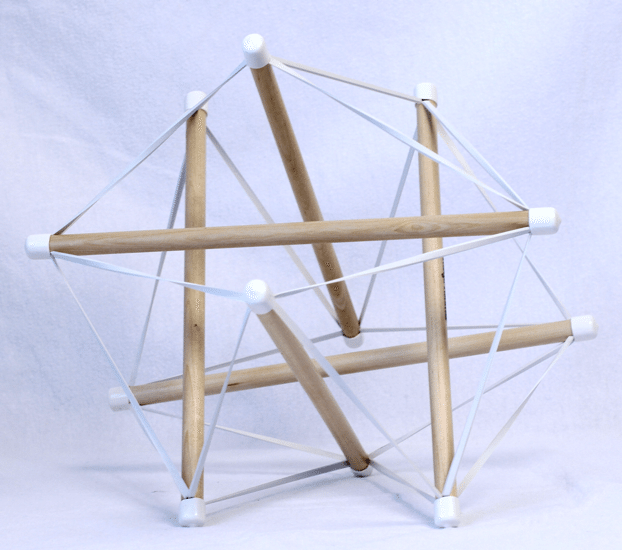

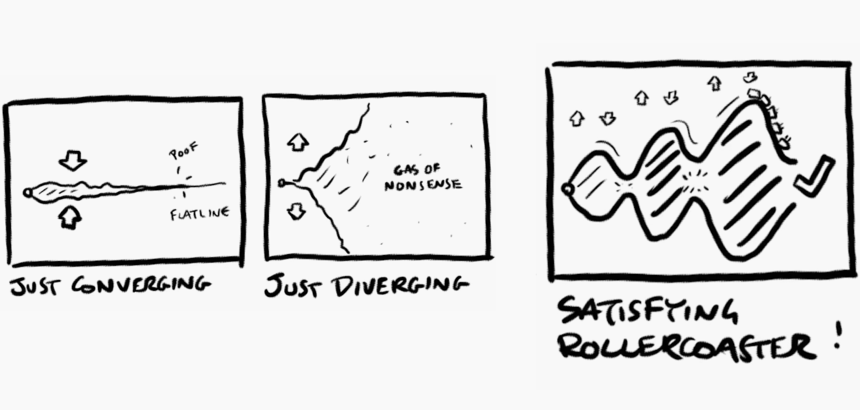

To me, these are wonderful game design challenges as they are about setting up a balance of mechanics that pulls the reality organically from the players, like a tensegrity, a force and counterforce that cantilevers story, emotion, and character out of the group mind.

In a future blog post I’ll dive into the concept of GM less games in more detail, but just for this one, let’s look at how the mechanics of plant talker balance out to bring into being Alex, our sweet dog rescuer.

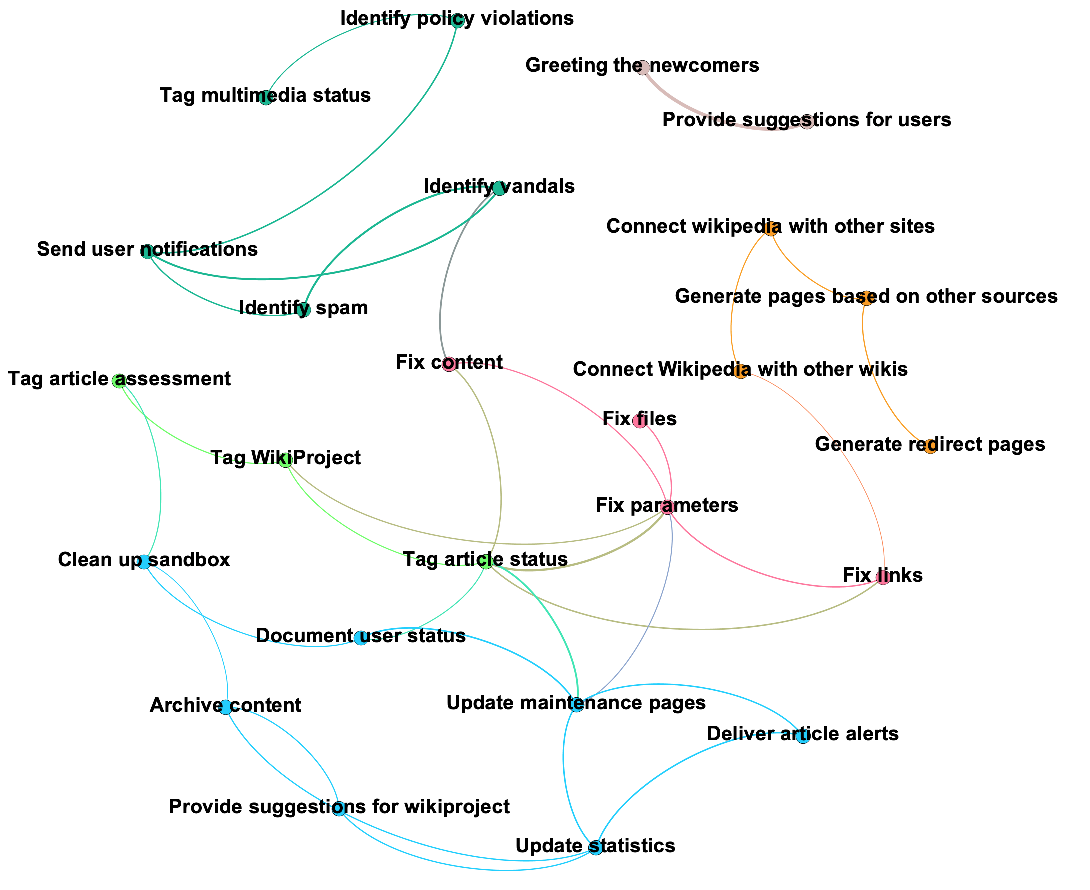

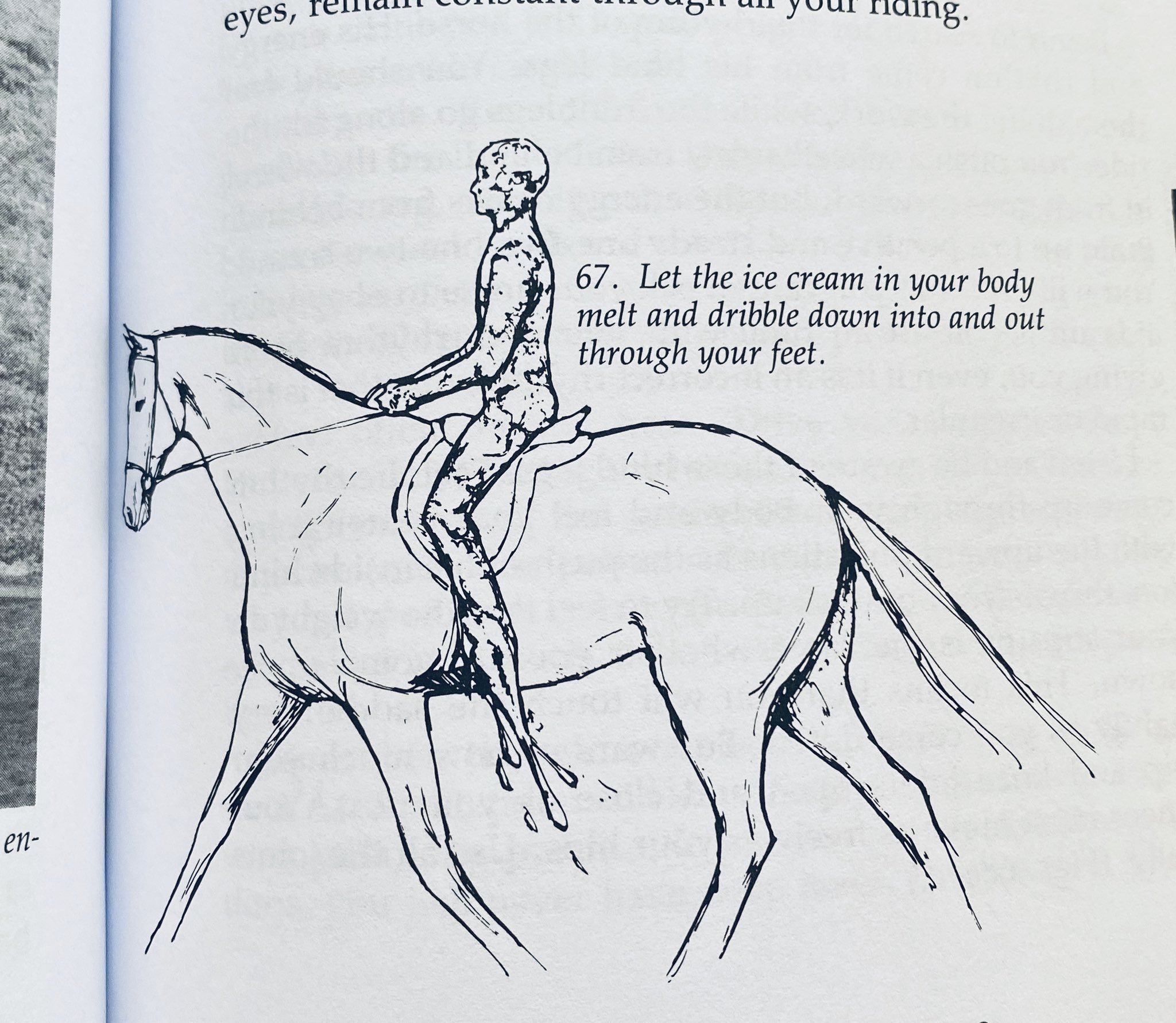

The starting point is this high level dynamic.

The basic rules are simple:

- Each player plays one plant, with a particular personality and care needs

- Each player also takes turns embodying the protagonist

- The game is driven by a deck of “Event” cards—breakups, new loves, a move to a new place, jobs, burnout, etc…

- Every scene is the protagonist alone in their apartment, in the aftermath of these events, monologuing or simply acting out what’s happening

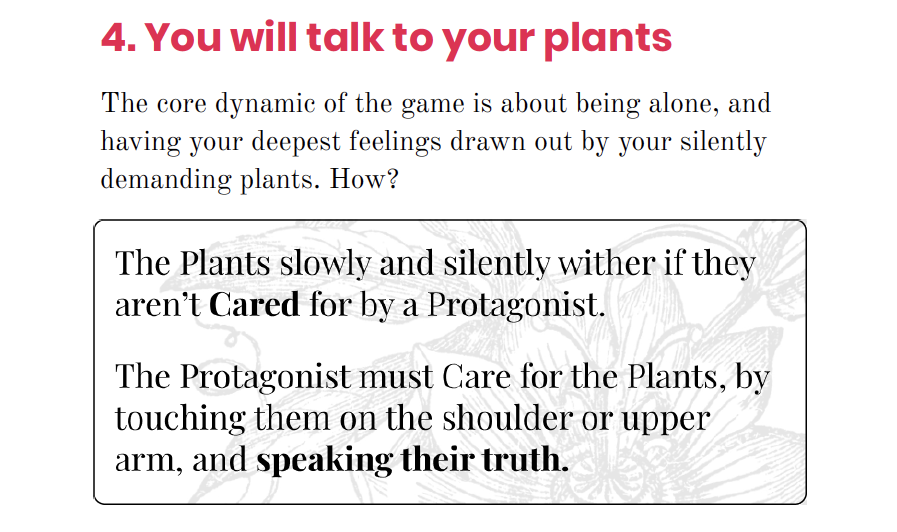

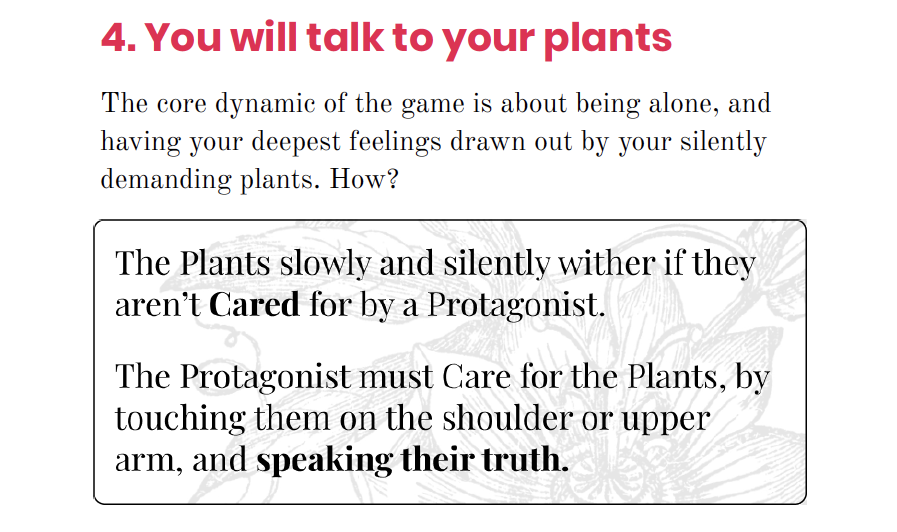

The dynamic between the protagonist and plants is designed to ratchet up the emotional stakes:

- Plants wither if not “watered”—players literally flop towards the ground to cry for help.

- But to actually help the plants, the protagonist “waters” them by touching them on the shoulder or upper arm and also “speaking their truth”. The plant only un-withers if they feel the protagonist is speaking out enough

- Plants have “Bloom” cards, with prompts that ask the protagonist to imagine specific life affirming memories from their past (moments of strength, courage, being loved, etc…). These can be handed out at any time, giving an emotional boost, and creative lifeline to the protagonist.

I was trying to create a system that pulls an emotional story out of the shared protagonist.

How do elements support the group mind?

Let’s look at a few key elements and how they might impact the group mind:

1. Explicitly shared protagonist, scaffolds the group mind

There is one protagonist, whose life is co-created by all the players. This allows players to feel like they don’t need to define everything. For example, in one scene a player just mimed sitting on the couch and watching TV, then became a plant again. It was a 5 second scene, but just right. This structure explicitly primes the group mind by predefining the canvas that the players are working on together. The game that opened my mind to the idea of shared protagonists was Downfall.

2. Greek Chorus, adds texture to the group mind

While the protagonist is monologuing, their plants act as a greek chorus, speaking gently to add little details freely, as “texture” to the protagonist’s work. This allows the protagonist to feel more comfortable with long silence or even having no idea what to say, because the plants can actively support with tiny details (in our game there was a recurring theme of the “Smell of mildew in the hallway closet” “Wind chime” “Kids playing down the street”). These little bursts of inspiration create wonderful texture for the group mind. This is a common improv technique, most notably in the group games you play at the start of a Harold.

3. Self paced prompts, deepen the group mind

Plants have specific tools to get the protagonist to push harder into their character. “Withering” is a little mechanical focal point. The bloom cards are more specific, and the specific prompts on them (e.g. “Tell a time when you felt strong”) create more structure for the protagonist. Most importantly, they are self paced. The plants can offer, but the Protagonist opts into them. Strong inspirations for this were Juggernaut and Underwater People, which both use cards to create self-paced character interactions.

I always struggled to truly let myself go in larps and improv, so I’m always grateful for systems like these that create explicit permission, so I end up pushing harder. It’s tough in the moment, but I’m so glad later!

4. Silence, gives the group mind space to breathe

This was the element I was most nervous about. I intended the game to be meditative, but it was something else to actually play it and find that we sometimes spent 5 or 10 minutes just sitting there as plants, not withering, not being the protagonist, just chilling, calmly. It’s a terrifying moment for a designer—in the silence, I had no idea whether people were enjoying the meditative experience, or were just utterly bored and stuck. In post-mortem, folks said it was relaxing. Whew! One player actually never chose to be the protagonist, and appreciated the possibility of a game that allowed him to play by just relaxing. Silence gives the group mind space to breathe.

This was inspired by an absolutely remarkable Fastaval larp by Mads Egedal Kirchhoff called Duel , which requires extended silence to the point where we spent ten minutes at the start just practicing talking slowly and atmospherically enough, with Mads interjecting “NO, MORE SILENCE” when we spoke too soon. It was amazing.

5. Workshops, help us leave behind our default way of interacting

All of these mechanics are a lot to internalize, and are a major change from how people interact in real life. To bring people in, I start the game with three short workshops, a technique inspired by Randy Lubin and Jason Morningstar’s “Honor Bound”. First, you practice asking simple questions of each other, and waiting 10 whole seconds before you speak. Second, you count to 10 together but one at a time, starting again at the start if two people say the next number at the same time. Finally, we practice gently adding sensory details. This is a crucial bridge from the normal social contract to the one in the game, and sets the stage for the group mind to appear.

6. Masks, align identities with the world of this particular group mind

Masks are dark magic. They create a distance, both for the wearer, who suddenly feels able to express emotions and feelings that might be off kilter from their normal personality. and for the person interacting with a masked player, who more easily treat them as a stranger or alien. Finally, there is the physical ritual that telegraphs: “Hey, I’m about to embody the protagonist”. It is customary to always look away when putting the mask on or taking off. This little detail makes the transition work that much better. The way masks break your normal identity makes it easier to slip into a new one that has an alibi to be in the group mind. This was heavily inspired by Old Friends—and of course by Keith Johnstone’s Impro.

And check out the incredible masks my good friend Amber Dean created for the day’s playing. Unbelievably awesome!

Back to the Death Star

Where my mind goes after these experiences is if any of these weird, lyrical patterns can change the way we interact with each other in the real.

Let’s say you have 6-7 co-workers and you have to solve something difficult together. Something contentious or requiring a great deal of creativity. Or the kind of thing where there might be enormous consequence to someone holding on to a thought for fear of “rocking the boat”. Ideally you have such trust and flowing group mind that you don’t need any of this! But not every group is there—and none start there. Could similar mechanics help overcome inherent politics and build that trust?

Will this work? Who knows! Let’s riff.

1/ Explicitly shared visualization surface

In a brainstorm with a product team (for example) there is already (ideally) the sense of shared ownership of a problem or project. But how might we make that even more literal? The protagonist in plant talker is the surface on which the reality is drawn. In a product meeting, that might be the whiteboard, or meeting notes. So let’s use that—perhaps there is a ritual way in which you explicitly sit down and can only speak when writing (one at a time). Does that slow down the group mind? Or does it create useful structure?

2/ Greek Chorus as supportive micro brainstorm

I come up with an idea (“Let’s build this widget”), and just like in the game we gently add details—not the literal ones but sparks of emotion (“It buzzes gently, like a fluorescent bulb”), how users might feel about it (“She feels nervous about bringing it home”), contexts where it might appear (“It sits in the back of the store, unbought, but imposing”)

Would this be super weird? Yep!

In a “serious” work context, we are expected to speak from our expertise, and certainly shouldn’t talk over each other. But expertise can be a trap when exploring new spaces. What might happen if we brought to bear our speculative abilities in imagining the ways a project might fail (the “pre-mortem”) or using storytelling to imagine possible user journeys verbally—the cheapest way to prototype. Here, adding such fragments of meaning might not be so off kilter. In fact, they are a gently amplified form of supportive listening.

3/ Self paced prompts as alibi for scary truths

There is the shy person in the corner, whose idea never sees the light of day unless a skilled facilitator brings it out of them. Or perhaps someone is cut short by an interruption—or self-doubt—and never regains their flow. How might the group have a structured way to help them push on?

The Bloom cards and way plants wither draw speech out of the protagonist, without forcing it out. What if you were discussing a tremendously difficult topic at work, the kind where people self-censor, or tiptoe around, and had a way for the group to indicate to a speaker that they were allowed to go further—perhaps a card with a prompt like “Say the thing that scares us”?

These kinds of mechanisms give you an alibi, because you didn’t come up with it. It was on the cards! This blunts our tendency to “shoot the messenger”.

4/ Silence as value

I recently heard David Lynch on a podcast say that every person in jail is someone who just needed another minute to think. In a meeting, you often feel like you have to speak to add value!

One of the most fantastic tools in meeting facilitation is to create structured moments of silence—the Delphi method is just one of those. I used to start staff meetings with 3 minutes of silence to give people time to reflect on what was important for that week, because I hated the way a standup made you feel “on the spot”. You didn’t remember the important thing, just the salient one.

But what happens if silence is allowed to happen as default, instead of being something that needs to muscle its way in? In Plant talker, the default is to say nothing at all, although you do have to train this! Which brings me to…

5/ Workshops

You wouldn’t do a difficult physical sport without warming up—at least not if you don’t want to get injured—yet how often do we warm up before difficult mental sport?

We tend to just jump in to cognitive situations, rushing to the finish line without thinking about whether we are in the right state to run the race. I used to record a podcast with three close friends, and we started every single recording session with an explicit warmup where we practiced give & take—not talking over each other. It slowed us right down, made us feel incredibly present; I remember our sessions as the best conversations we ever had.

What do “warmups” mean, for the groups we are part of?

6/ Masks

How often do our roles—for example UX, PM, Eng—how often do these unintentionally design a game that we would not choose to play? Masks are a temporary, quasi-mythical in their strength redirection of these kinds of forces, dangerous and a bit wild. Probably not appropriate for non-game settings.

But the metaphor of the mask is useful! What ritualistic ways might there be to “mask” workplace roles, or temporarily replace them with different ones. Fictional ones?

A cute example of this: the anonymous animals of Google Docs… Perhaps you can’t imagine wearing a mask in a grey conference room on a Monday morning. But get in front of your computer or phone, and you suddenly own as many masks as there are apps installed, each one a slightly face.

And this is the crux of this piece. There is a ton of prior art in areas like meeting facilitation, running sprints, organizing workshops, with basic, egregious things to correct for first (taking care to avoid quarterbacking, supporting introverts, men not talking over women). Makes sense to master that before getting too weird.

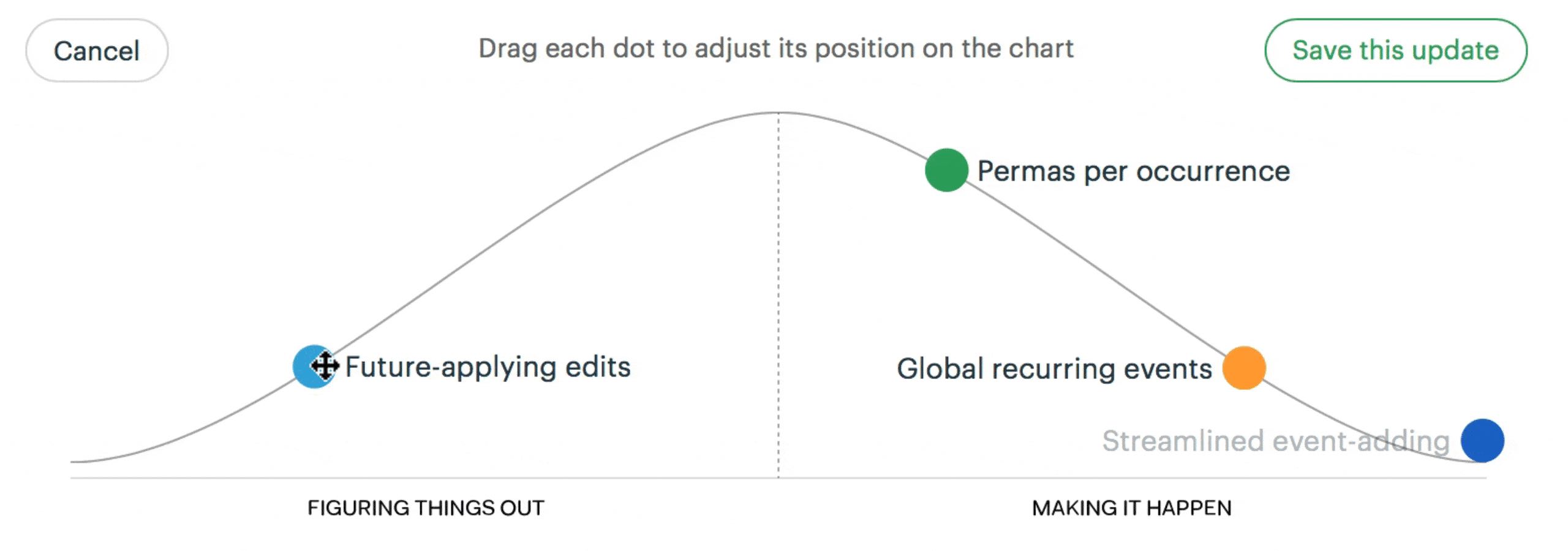

But as I explored in my last essay on Figma, I believe we are just scratching the surface of social norms in digital spaces, where things like identity, communication, and space itself have to be written from scratch. Human society is constantly generating and regenerating new places and ways to interact, so what might seem weird right now might lead to a boringly standard practice a couple decades later (jogging!).

Opening possibilities

What I’m hoping to highlight here is that there are many paths to the group mind, and that games create a safe, lyrical container to explore some of the stranger trails.

How do these different mechancis affect the group mind? Its intelligence? Its emotionality? Its ability to solve problems, to help narrow down? Its ability to go broad, generate the new? Its ability to make people feel safe?

What kind of group mind do different combinations of these mechanics manifest?

Back in the day to day world, there is still a game being played, except it’s one dictated by emergent culture and norms. The game can be shaped—as is blindingly clear from the vast difference between a well and poorly run meeting or workshop—but the dynamic range of that shaping is limited by people’s expectations.

I hope that this very rough essay shows how vaguely psychedelic mechanics about masked plants can actually be brought to bear in these more serious contexts, to make them weird again. The mechanics may be socially awkward, wildly impractical, and a lot of work to experiment with, but… well there’s no but. That’s kind of the point!

And the payoff: being part of a group mind that can hear the music, and maybe write new melodies that no individual could have written.

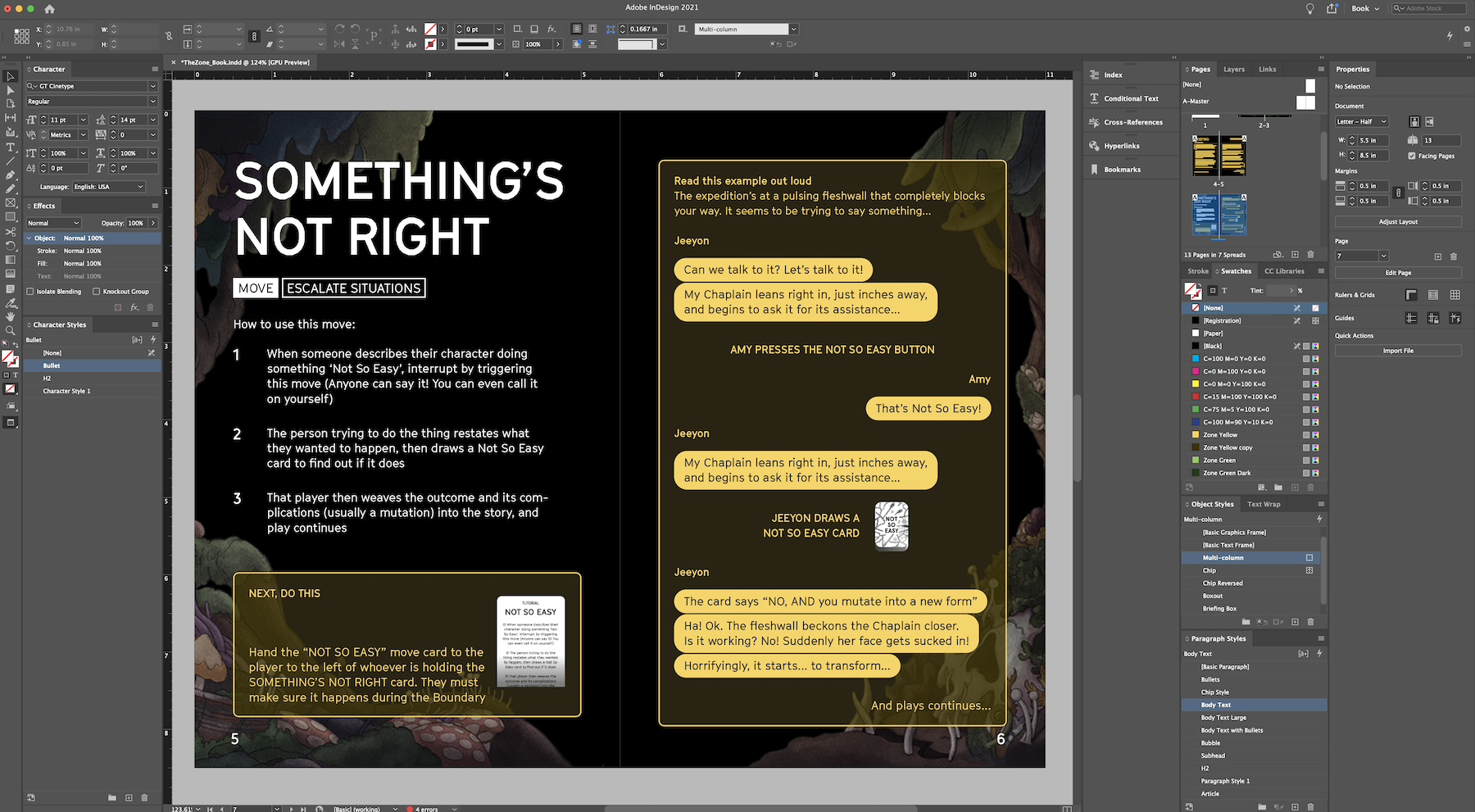

I expect these to be either 2 page spreads with just a new briefing and some guidance on how to change the decks, and probably also a few 4 page spreads to make space for a generator table (or two) and awesome art. These mostly won’t be written by me—I want to hire (paid of course) from the community to make these storyseeds as weird and diverse as possible.

I expect these to be either 2 page spreads with just a new briefing and some guidance on how to change the decks, and probably also a few 4 page spreads to make space for a generator table (or two) and awesome art. These mostly won’t be written by me—I want to hire (paid of course) from the community to make these storyseeds as weird and diverse as possible. The results are incredibly variable but exactly the kind of thing I hope to evoke: non-human surrealism that somehow seems to mean three things at once (which is convenient because each card has 3 totally different prompts on it).

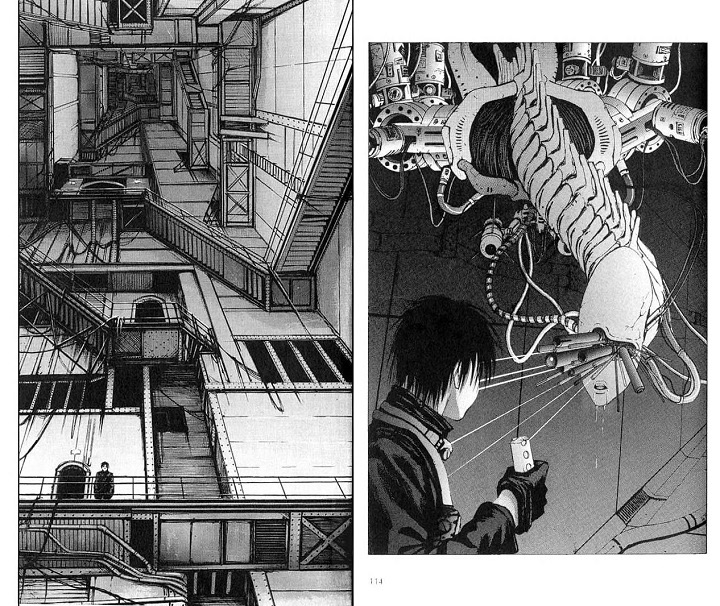

The results are incredibly variable but exactly the kind of thing I hope to evoke: non-human surrealism that somehow seems to mean three things at once (which is convenient because each card has 3 totally different prompts on it). It seems to know certain styles more than others. For example, somewhere in the 400 million images CLIP learned from was probably some of the work of amazing Polish surrealist painter Zdzisław Beksiński. So I could ask it to use that as an influence. Here’s what I got by entering the text from the Location cards for “The Mall”, “The Hospital”, “The Military Base”, and “The Swamp”.

It seems to know certain styles more than others. For example, somewhere in the 400 million images CLIP learned from was probably some of the work of amazing Polish surrealist painter Zdzisław Beksiński. So I could ask it to use that as an influence. Here’s what I got by entering the text from the Location cards for “The Mall”, “The Hospital”, “The Military Base”, and “The Swamp”.

Luke, with a force ghost in his brain. Yeah, it’s kinda like that.

Luke, with a force ghost in his brain. Yeah, it’s kinda like that.

This seems like a good time to reference Seanan McGuire’s awesome spectrum of alternate worlds from her book “

This seems like a good time to reference Seanan McGuire’s awesome spectrum of alternate worlds from her book “